(Ho Chi Minh City)

(Ho Chi Minh City)

"... a French city flowering alone out of a tropical swamp" —Osbert Sitwell

Like Shanghai or Bangkok, Saigon comes imbued with its own myth — and you may have a vision in mind already. You've seen it on television, you've seen it in movies: the city of war, the city of sin, the city of changing fortunes. However, the Saigon of today bears little resemblance and is now busy and brash, the growing commercial hub of Vietnam with towers rising across the skyline, and the modern industrial muscle of the nation. It's a city of economic contrasts, like so many others in the region where at temple festivals you'll see women in shimmering silk ao dais float by ragged beggars. Once Southeast Asia's largest city, it's now boom time again and Saigon is well on its way to recapturing that crown.

Saigon History

|

Little is known of Saigon's early history, and the origins of the city's name are uncertain. In the 15th century Saigon was little more than swampland in a forest wilderness, an area under the Khmer sphere of influence. The Cambodians hunted in this area, then called Prei Nokor. Slowly it grew into a small market town; as forest was cleared and rice paddies were carved out, it became an outpost on the eastern flank of the Angkorian Empire.

As the Khmer and Cham Empires shrank, the Vietnamese advanced from the north. In the early 17th century, on the condition they be allowed to settle the south, the Vietnamese agreed to help the Khmers fight the Thais. Fully in control by 1680, the Vietnamese allowed 3,000 refugee Chinese Ming soldiers to settle the area of Bien Hoa. A few years later the Chinese started a market at Cholon. Eventually, the Khmers were pushed back to the Mekong Delta.

Saigon continued to grow as Vietnamese settlers arrived from the north, spreading out along the delta waterways and clearing forest. The settlement became the administrative center of the region, a trade base and tax-collecting center. Gia Dinh, a small fort housing the area governor and his administrators, was built. In the 17th century, factions of the Nguyen clan were crushed by a peasant revolt led by the Tay Son brothers, who captured Gia Dinh. Then, in 1788 Nguyen Anh, with the help of the French Jesuit missionary Pigneau de Béhaine along with an army of French mercenaries, recaptured Gia Dinh. Two years later, Nguyen Anh conscripted a force of 30,000 laborers and set about building a large Citadel in Gia Dinh, in the area between what is now the zoological gardens and Reunification Hall. The octagonal Citadel was based on a French military design with its center a Royal Palace. When Nguyen Anh proclaimed himself Emperor Gia Long and moved the court to Hue, the trappings of royalty were transported north, with Saigon serving as a base for governing the southern third of the country.

Saigon, New and Old |

By 1800 Saigon grew to a population of 50,000. In 1835 a peasant revolt at Gia Dinh was put down by Emperor Minh Mang, who then razed the Citadel and erected a small fort. The emperor and his successors blamed French missionaries for peasant uprisings, and when French and Vietnamese priests were executed, the French used this as an excuse to invade the country. In 1859 a French force of eight battleships and 2,000 troops started up Saigon River. The French used explosives to breach the walls and capture Saigon. During counterattacks by the Vietnamese, the fort was destroyed. The bulk of the population was moved out to the country, leaving about 25,000 residents left. Shortly thereafter, the French established the colony of Cochinchina, with Saigon as its capital.

Using forced labor, the French built a new city of boulevards and buildings in what is now Central Saigon. Public works like the post office and governor's palace were initiated. Notre Dame Cathedral was completed in 1883, built upon the site of the former Citadel's arsenal. There were hotels and villas for businessmen and administrators; canals were filled in to make roads. Towering tamarind trees lined the boulevards and palms graced the villas-now rain stained and moldy from years of neglect.

The population of Saigon has fluctuated with its changing fortunes. In 1962 the city's population was only 1.2 million; by the late 1960s it had swelled to over three million. After 1975 the population decreased as ethnic Chinese fled the country. The population of Saigon now exceeds six million residents. Many new arrivals come from the countryside-the average income in Saigon is more than four times higher than in rural areas. Most Saigon residents seem to own either a bicycle or a motorcycle, making this a tricky place for pedestrians. One startling fact: there are over five million scooters in Saigon.

Today Saigon is the major manufacturing and distribution center of southern Vietnam. Industries tries include shipbuilding, leather tanning, and the manufacture of bicycles, textiles, and traditional handicrafts.

Name Game

People are schizoid about the name of this city. It's been called Gia Dinh, Ben Nghe, Ben Thanh, and half a dozen other names. In 1975 communists victors put their stamp on the place, changing the name from Saigon to Ho Chi Minh City. To Vietnamese, it's officially now Thanh Pho Ho Chi Minh; in French it's Ho Chi Minh Ville, sometimes shortened to "Hoville." In English print, the city often turns up as HCMC, or HCM City, which is shorter, but not any easier to pronounce or comprehend.

Ho Chi Minh City hasn't stuck with everyone, even with officialdom — it's Saigon Tourism you'll see on the sign, not Ho Chi Minh City Tourism. Because of the failure of the general populace to embrace the name Ho Chi Minh City, the authorities have compromised, dubbing the central district Saigon or"District 1. ("Quan mot")

Ho Chi Minh City now refers to the greater metropolitan area, comprising 12 quan-urban districts-and six suburban districts. Ho Chi Minh City is one of the three independent municipalities in Vietnam, the others being Greater Hanoi and Greater Haiphong. Central Saigon refers to Districts 1 and 3, the downtown business core with high-rise hotels and landmark French buildings like the old Hotel de Ville (City Hall) and Notre Dame Cathedral. District 3 is an exclusive zone of government offices, renovated French villas, and tree-lined streets. Districts 5 and 6 are Saigon's "Chinatown." These are commonly referred to as Cholon, although officially this name does not exist. Cholon used to be separated from Saigon, but grew until it melded into it. The Chinese presence is evident in Districts 8, 10, and 11 as well.

Saigon Highlights

Saigon City Hall |

COLONIAL SAIGON

Colonial Saigon can be explored by cyclo, bicycle, motorcycle, taxi, or even foot. Cyclos are a leisurely way of getting around-and you will go the long way round, because cyclos were banned from over 50 streets in the city center in mid-1995 to ease traffic congestion. If on a bicycle or motorcycle, watch for one-way streets, and be wary of rush-hour traffic-the boulevards can be thronged, making it difficult to turn at major intersections.

Casting yourself back to 1930s and 1940s Saigon is easy. The grand colonial edifices still stand dwarfed, it's true, by newer high rises but nonetheless providing sufficient illusion for the time traveler. In fact, Saigon functions as a large outdoor museum of French colonial architecture, some of it plain and ugly, others majestic. The buildings also serve as navigation landmarks, particularly the cathedral and the Hotel de Ville (right).

Norman Lewis described 1950 Saigon in A Dragon Apparent:

A French town in a hot country.... Its' inspiration has been purely commercial and it is therefore without folly, fervor or much ostentation. There has been no audacity of architecture, no great harmonious conception of planning. Saigon is a pleasant, colorless and characterless French provincial city, squeezed onto a strip of delta-land in the South China Seas. From it exude strangely into the surrounding creeks and rivers 10 thousand sampans, harboring an uncounted native population.... The better part of the city contains many shops, cafes and cinemas, and one small plain cathedral in red brick. Twenty thousand Europeans keep as much as possible to themselves in a few tamarind-shaded central streets and they are surrounded by about a million Vietnamese and Chinese.

Saigon has little in the way of native architecture, barring pagodas and Chinese-style shop houses.

HONORED FRENCH

Not all the French were rubber-plantation slave drivers. A few are actually honored with street names. Near Reunification Hall is Duong Alexandre de Rhodes, named for the 17th-century French Jesuit who introduced romanized script into Vietnam. This is in fact the original French name for the street; during the 1980s, the street was renamed after national Vietnamese hero Thai Van Lung, but in 1995 it was decided to restore the name Alexandre de Rhodes. Thai Van Lung is still on the map-the name simply bumped another street off the map farther east.

Duong Pasteur is a nod to Louis Pasteur, who established medical research institutes around the world to fight disease. Duong Pasteur features a Pasteur Institute (Vien Pasteur) at the north end. Two other Saigon streets with French names are also related to Pasteur-Rue Calmette and Rue Yersin, both named for proteges of Pasteur. Dr. Albert Calmette established a research lab in Saigon in 1890, and Dr. Alexander Yersin set up a lab in Nha Trang in 1895. These were the first Pasteur Institutes established outside Paris. There's also a Rue Pasteur and Rue Yersin in Nha Trang. Another Pasteur protegee, Marie Curie, is also honored in Vietnam. Marie Curie School has changed little since its founding in 1918. The archway still bears her name, though Ecole Marie Curie has been changed to Truong Marie Curie. Located at 159 Nam Ky Khoi Nghia, the high school is attended by a thousand students studying English and French.

The city was largely built by the French. When the French captured Saigon in 1859, the area was swamp and marshland. They set about filling in canals, draining marshlands, and building roads, tree-lined boulevards, an opera house, court, arsenal, customs houses, cinemas, and schools. For entertainment, the French introduced exclusive sports clubs, glitzy casinos, and sleazy opium dens. Down by Saigon River lay the offices of the shipping and communications company Messageries Maritimes. At 74 Hai Ba Trung Street sat the state opium factory.

Saigon of the 1930s was cleaner and leafier than it is now-the French took great pride in their manicured lawns and botanical gardens, now the zoo area. They planted the tamarind trees that shade Saigon boulevards and break up the monotonous architecture. The French left behind their cars, too. In among the throng of cyclos and motorcycles plying the streets you might stray across a Citroen Traction, the 1930s classic French car with running boards. Traces of the French presence linger in the food as well. Sitting in a cafe you can crack open a BGI, joint venture French beer not far removed from the original beers of French Indochina-and indulge in a baguette with pate.

Hotel de Ville

The Hotel de Ville, at the northern end of Nguyen Hue Boulevard, still serves as Saigon's City Hall. With its ornate gingerbread facade, the Hotel de Ville looks like the town hall of a French town. Considerable debate raged over its design and location before it was finally completed in 1908. Today it's called the People's Committee Headquarters, but neither the people nor visitors are allowed to see the interior, where crystal chandeliers hang.

If you want to walk around this area, park your transport in the garage at number 155 near the Rex Hotel, used by taxis, tour buses, motorcycles, and bicycles. The original iron grillwork exterior is still intact and is possibly of German origin.

Big French stores like Les Grands Magasins Charner once lined Nguyen Hue Boulevard, then Boulevard Charner. Its motto: "We supply you with every requisite for colonial life, at the lowest prices." Little has changed in this corner of Saigon, except for the addition of a large statue of Ho Chi Minh cradling a child, located on the strip of greenery facing the Hotel de Ville. A few red flags flutter from the building.

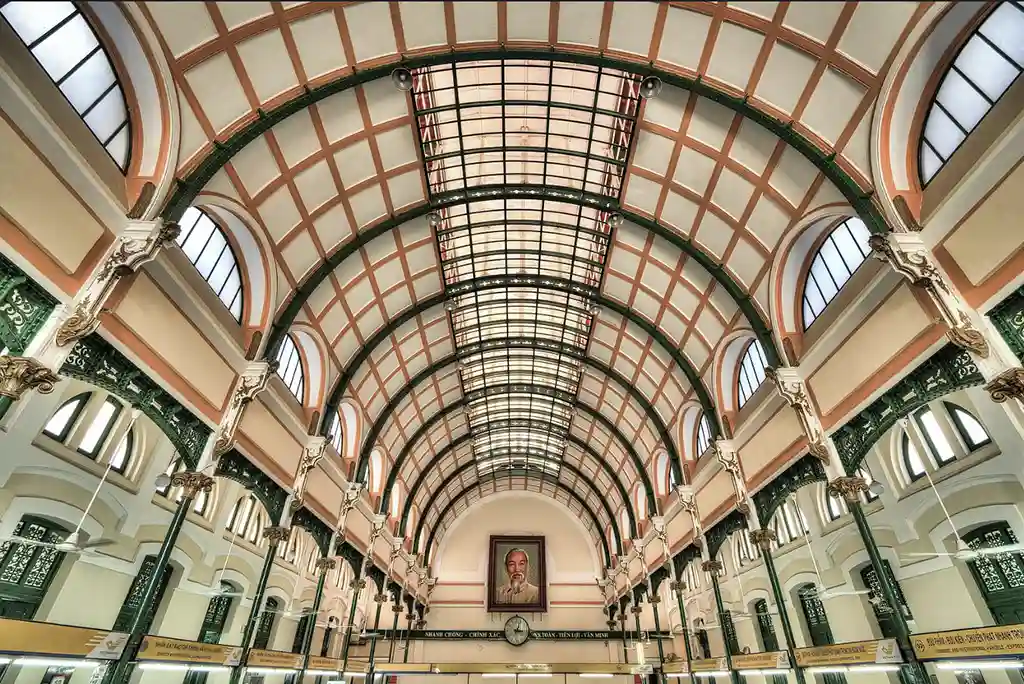

Saigon Central Post Office

Step back in time and visit one of the most the Saigon Central Post Office which stands as one of the world's most graceful and elegant postal buildings. Reflecting the architectural charm of the French colonial era in Vietnam, it showcases a stunning facade characterized by vibrant yellow walls, graceful arched doors and windows, and intricate decorative reliefs. While many mistakenly attribute its design to the renowned Gustave Eiffel, it was actually the brainchild of French architect Alfred Foulhou. The post office welcomed its first visitors on January 13th, 1863, marking the issuance of its inaugural stamp. Boasting a neoclassical design, the structure impresses with its expansive interior adorned with painted arching ceilings, intricately patterned tile flooring, and exquisite decorative features. Not to miss.

Neoclassical Grandeur

The Revolutionary Museum, at 65 Ly Tu Trong, used to be the mansion of the French Governor of Cochinchina; under President Ngo Dinh Diem, it was known as Gia Long Palace. This is one building where you can see the interior. The neoclassical building itself and the grounds actually hold greater interest than the museum displays, which you'll see repeated in many military museums in Vietnam.

Downstairs are former ballrooms with high ceilings; a grand sweeping staircase leads to the upper salons. Downstairs you'll find random displays from the 1850s to 1940s including some pictures of old Saigon; memorabilia upstairs recalls the 1940s to 1960s and Vietnam's struggle against the French and Americans. Of interest here are displays of propaganda leaflets urging GIs to hurry home.

Outside, a parked Huey UH-1 helicopter overlooks landscaped lawns and gardens. Under the helicopter is a bunker with six meeting rooms and a tunnel leading to Le Thanh Ton Street and Reunification Hall. It was built in the 1960s under the Diem regime. Also on the grounds are artillery pieces, two small planes, and a Russian tank used in the 1975 assault on Saigon. The Revolutionary Museum is open 0800-1130 and 1330-1630, closed Monday. Free entry. Opposite the museum is a tranquil park and a cafe serving refreshments.

Due to the one-way streets here, you go against the grain to reach the museum. If on a bike, you can either get off and walk it to the museum, or loop around the block north of the museum, circling past the Palais de Justice.

Cercle Sportif

From the museum, circle up Rue Pasteur, turn left on Nguyen Du, and loop around the back of Reunification Hall to Nguyen Thi Minh Khai Street. Step inside a north entrance, and you'll find ghostly traces of French presence in a dilapidated sports club, once the Cercle Sportif. The French set up a chain of Cercle Sportif clubs in Indochina; these clubs, of course, were exclusively French, with no Vietnamese allowed. Today the old Cercle Sportif building is part of a Vietnamese youth recreation club. You can still make out the Cercle Sportif logo, a C entwined with an S inside a circle, carved in wood at the former clubhouse entrance. The clubhouse overlooks tennis courts and a small outdoor cafe. Farther back is a vintage full-length swimming pool, surreally framed by Grecian columns; trellised areas and plants shelter wicker chairs. There are two wading pools here, and a place still known as the Cercle Gym, housing the Cercle Cafeteria. Adjacent Van Hoa Park used to be Jardin de la Ville; it was turned over to a the public by the French governor in 1869.

East of the Cercle Sportif is Le Quy Don School, formerly the French school Lycée

Chasseloup-Laubat. The school was featured in the movie The Lover.

Notre Dame Cathedral

Notre Dame is a Gothic cathedral with twin brick towers tipped with iron spires and flying buttresses, all faithfully reproduced in tropical Vietnam. All the parts were shipped from France. The cathedral was built between 1877 and 1883. It's a prominent Saigon landmark often featured on postcards. Services are held here six times on Sunday, and several times during the week. Go inside to view the stained-glass windows; the cathedral is open 0700-1100 and 1430-1630 weekdays. The cathedral overlooks a statue of the Virgin Mary in a small square once known as Place Pigneau de Behaine, named after an 18th-century missionary who lobbied for French military intervention in Cochinchina.

Facing onto the same square to the east is the General Post Office, built in the 1880s. It looks pretty much the same today, apart from a red flag waving outside, a couple of big antennae sprouting on the rooftop, and, inside, a large Ho Chi Minh portrait presiding over the proceedings. Go inside to see the large glass dome and long vaulted ceiling. On the outside, little plaques bear the names of distinguished French: Descartes, Voltaire, Ampere.

Municipal Theater and the Hotel Continental

On Dong Khoi Street a few blocks southeast of Notre Dame Cathedral lies the Municipal Theater, also known as Saigon Concert Hall. Originally built in the early 1900s, it was renovated in the 1940s. After 1956, the building housed the lower division of the National Assembly. Today the theater is used as a venue for traditional theater, gymnastics displays, and rock concerts. The interior is not as elaborate as the exterior suggests. Although there are plush red chairs and fancy wrought-iron banisters, there's hardly anything in the way of ceiling decoration. For bike or motorcycle parking, go to the back of the theater to the east side.

Facing the Municipal Theater is the Hotel Continental, a French hotel magnificently restored to its full colonial grandeur. The hotel was originally constructed in 1885 by the Societe des Grands Hotels Indochinois, part of a chain of elegant hotels also found in Hanoi, Hue, Vung Tau, and Phnom Penh. The sidewalk terrace outside the Continental was a popular rendezvous spot for highbrow French society. In the 1980s, the terrace bar was glassed in and transformed into an air-conditioned Italian restaurant. Graham Greene featured the terrace in his novel The Quiet American. Somerset Maugham described it in The Gentleman in the Parlour (1930):

Outside the hotel are terraces, and at the hour of the aperitif, they are crowded with bearded, gesticulating Frenchmen drinking the sweet and sickly beverages.... It is very agreeable to sit under the awning on the terrace of the Hotel Continental, and with an innocent drink before you, read in the local newspaper heated controversies upon the affairs of the colony.

The "heated controversies" included how to treat domestics (should one hit them?) and how many hours to spend in siesta (two or three?). Beyond domestic worries, the French tended to business affairs and the pursuit of leisure. After work a round of absinthe, a visit to a restaurant, the theater, and possibly a trip to a casino, brothel, or opium den. Their decadent lifestyle led to another big problem-large unpaid tabs.

Dong Khoi Street |

Along Dong Khoi

Dong Khoi Street is a classy shopping thoroughfare with antiques, jewelry, Parisian fashions, and perfumes. During the French era this was Rue Catinat, an exclusive shopping area as well as the haunt of spies, French police inspectors, and Annamese beauties. It was also the site of occasional terrorist cafe bombings. During the Vietnam War, the street became To Do (Freedom Street), a red-light district, and was renamed Dong Khoi (General Uprising) Street after 1975.

Though it's seen better days, Dong Khoi Street still has an exclusive air about it, with art galleries, gift shops, lacquerware shops, and a few chic cafes. On the east side of Dong Khoi art shops sell hand painted reproductions of famous canvases. For insight into this curious industry, go past the Dong Khoi Hotel and turn east on Ngo Duc Ke; here you'll find a whole workshop of oil artists-some 20 of them-busy touching up their Monets, Gauguins, Van Goghs, and Picassos. Everything down to that Mona Lisa smile or Gauguin breast is copied from art books by graduates of the Fine Arts School of Ho Chi Minh City. A canvas that takes a week to copy starts out at $80-100, while a six-week effort may yield a hefty $600. Custom-made canvases can also be ordered.

The hotels along Dong Khoi are mostly operated by Saigon Tourist. The outfit makes select renovations, often in joint ventures. A classic that was renovated in 1997 is the Dong Khoi Hotel, at 8 Dong Khoi, which back in the 1920s was called the Saigon Palace. The lobby features the original spiral marble staircase; the rooms have cavernous bathrooms. Down by the Saigon River the Hotel Majestic has also seen extensive renovations. This old French hotel at 1 Dong Khoi is known in Vietnamese as the Cuu Long, or River of the Nine Dragons. Go to the 5th floor Sky Bar-it has the original marble floors, and affords great views of Saigon River.

Charles de Gaulle told John F. Kennedy that Vietnam was "a bottomless military and political swamp." He forgot to mention the moral quagmire. American soldiers who fought in Vietnam paid a double price for a dumb and immoral foreign policy: they fought the war, then weathered the stigma of defeat and disfavor at home. Faced with these unpleasant truths, a number of Vietnam vets have returned to Vietnam as a healing process, to lay to rest the uneasiness that

In 1993 two shops opened on either side of the gates at the War Crimes Museum, each called Wartime Souvenir Shop (that signage has since been removed, but it sums up the trade here very succinctly). Apart from the standard stock of T-shirts, the proprietors sell a rather bizarre collection of souvenirs. How about a flower vase made from a 40mm cartridge, burnished to a bright gold? Or a pair of Ho Chi Minh tire-tread sandals? Perhaps a green NVA pith helmet or NVA campaign and victory badges? Other items on sale include lighters made from M-16 cartridges and small oil lamps the Vietcong recycled from M-79 cartridges and used to illuminate tunnels. There's even a set of Vietnam in Wartime postcards, one featuring a Vietcong woman in full combat gear, striking a heroic pose.

You can also buy U.S. flashlights, watches, compasses, and field glasses. And there's a range of rusted U.S. dog tags with name, religion, and blood type embossed on each one. Authentic? Probably not. Certainly morbid.

U.S. army-issue Zippo lighters cost $5-20 depending on "quality" and whether or not they work. Many antique and souvenir shops in Saigon, as well as shops at Dan Sinh army surplus market, carry Zippos. Some feature a poignant, prayerful, military, romantic, or obscene slogan; others bear engravings such as nude women, Peanuts cartoon characters Snoopy and Lucy, or the bearded Zig Zag rolling-papers man.

During the Vietnam War, aluminum cans discarded by U.S. soldiers were turned into hand grenades by the Vietcong. This came as a shock to American troops, who began to be more careful about what they threw away. The Vietnamese are still transforming those cans. At the Wartime Souvenir Shop and on the streets of Saigon, you can buy tanks, Huey helicopters, F- Phantom jets, F111s, and Cessnas made of old Coke, Tiger, or Heineken cans. These origami-in-metal pieces sell for a dollar and feature painstaking detail, the helicopter doors are even detachable.

War materiel is recycled in the oddest places. Once, when I mentioned the war, my cyclo driver, a former ARVN soldier, pointed at his bicycle bell-a large brass cylinder struck with a small handlebar-operated device, like a gong. I took a closer look: the bell was made from a 105mm shell case, cut off at the bottom.

Vietnamese, for their part, had trouble understanding exactly why the Americans interfered in their affairs. Still, they treat returning U.S. veterans the same as any other tourists-they bear no grudge. It's really the Vietnamese who should be bitter about the whole thing, but they're not. Life goes on.

War Remnants Museum

To take a shattering leap back to the wartime 1960s and I 970s, visit the War Crimes Museum, open daily, including holidays, 0730-1145 and 1330-1645, on Vo Van Tan near the intersection of Le Quy Don. Following new relations with the United States, the name of this place was changed to "War Remnants Museum," and by the time you get there, it may have changed again, who knows? The official HCMC City Map of 2000 calls it the "Museum of Aggressive War."

To get there from downtown Saigon, take Pasteur Street north and turn left on Vo Van Tan. The museum is on the grounds of a French villa that once housed the U.S. Information Service. The villa is not used for displays-these are located in four salons close by. This small museum is grisly, horrifying, sobering, and deeply disturbing. Few English captions accompany the pictures on the walls, but the photos speak for themselves-the My Lai massacre, victims of an 3 anti-personnel weapons like napalm and Agent Orange, deformed babies. A series taken from the Chicago Sun- Times shows a Vietnamese POW being pushed from an American helicopter. This raises the ethical questions regarding war crimes: where does "normal" war end, and where do war crimes begin? There is a photo parade of the guilty, from Lyndon Johnson to Richard Nixon, pictures of U.S. and European antiwar demonstrations, a display of eight medals sent to the museum by American vets in 1990. On display are American infantry weapons used in Vietnam. And in one salon is a picture of General Giap greeting former Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara in November 1995, after he announced the whole war was a terrible mistake. There used to be a Chinese atrocity wing in this museum, related to the border wars of 1979. After Vietnam normalized relations with China, the display was discreetly removed. In the meantime, two Wartime Souvenir Shops popped up, selling Zippo lighters, war memorabilia, cobra wine, T-shirts, water puppets, and other odd items.

Around the grounds you'll find an array of captured weaponry-M-41 tank, 175mm howitzer, M-1 13 flamethrower, A37B light bomber, U17A observation aircraft, and a few Huey helicopters. There's also a French guillotine, brought to Vietnam in the early 1900s. As late as the 1950s it was hauled around the provinces to publicly decapitate Vietminh resistance fighters in the French colonial manner. After normalization with the United States, exhibits at the War Crimes Museum were rearranged and modified, and the authorities decided to take another crack at the French by putting up a replica of several cells of the notorious French prison of Condao, complete with models of "tiger cages," and pictures of torture methods. These same prisons were taken over by the South Vietnamese regimes and used to torture captured North Vietnamese-strangely enough, the exhibits focus more on the Diem Regime era rather than the French era.

The War Crimes Museum is an odd place to stage entertainment, but as the biggest tourist draw in Saigon, it's somehow logical. There are 20-minute water puppetry performances in a small on-site theater, and performances of traditional Vietnamese music in another salon.

American Haunts

From the War Crimes Museum, head east until you reach an odd traffic circle. American civilians once occupied apartments around the circle, an exclusive residential zone. In the middle of the circle stands a shaft of concrete. At first glance this appears to be a piece of Socialist sculpture and there's a surreal flight of stairs to one side. Apparently there was once a statue of a sacred tortoise mounted on top of the concrete pillar, but it was blown up by disgruntled Vietnamese. Around the traffic circle are lots of open-air cafes where you can sit and contemplate the damage. Inside the derelict area a set of fountains have been installed, turned on for photo opportunities on special holidays.

Vietcong terrorists sometimes turned Saigon t into a battlefield, bombing businesses patronized by Americans. Despite these attacks, Saigon was one of the safest places to be during the Vietnam War, and its legendary bars, restaurants, and hotels were the dreams of GIs in the field. Some of the places they frequented still thrive. The Rex Hotel was used by U.S. officers, as was I the Majestic; war correspondents gathered to s watch the war on the roof of the Caravelle Hotel; Maxim's nightclub was the same overpriced dive I it is today.

The American Consulate

On Le Duan Boulevard, Vietnamese mill around the entrance of the U.S. Consulate, queuing up to apply for U.S. visas or immigration papers. Deja vu of sorts: the present cream-and-green consulate building was constructed in 1999 in the same walled compound as the old wartime embassy. The six-story American Embassy of wartime days was completely demolished and turned into a garden area that adjoins the present U.S. Consulate.

The Americans moved the embassy to this site in 1967 after the previous location was blown up by a 100-kilogram car bomb. But the new fortress-like building on Le Duan was not enough to stave off an attack: a 17-man Vietcong commando unit stormed the embassy on January 31, 1968. The commandos, dressed as South Vietnamese soldiers, were killed, along with five American Marines and MPs.

The U.S. Embassy closed on April 30, 1975 when the last of the staff boarded a helicopter from the roof as Saigon fell around their ears. The last chopper lifts were hectic. Thousands of Vietnamese who had worked for the Americans had been promised a lift out, but the United States reneged and they were left behind. The furious Vietnamese sacked the embassy. In All the Wrong Places, English writer James Fenton recounts, "The place was packed, and in chaos. Papers, files, brochures, and reports were strewn around.... One man called me over to a wall safe i and seemed to be asking if I knew the number of the combination. Another was hacking away at an air conditioner, another was dismantling a t refrigerator." In their rush to get out, American - embassy staff left behind files on those who t worked for them, making it easy for the north to identify collaborators.

Although the embassy was razed in the late 1990s, a few relics were salvaged-including the set of portable stairs leading up to the last choppers to evacuate. Those were removed to Washington's Smithsonian Institute.

Military Museum

The main target of Vietcong tanks rumbling through the capital was not the U.S. Embassy but the gates of the Presidential Palace, three blocks to the west. Americans remember the last helicopter leaving the U.S. Embassy, but for the Vietnamese the key image is that of tanks smashing down the palace gates. The tanks then rolled onto the lawn, formed a semicircle, and fired a salute.

The Vietnamese point of view on the war is presented at the Military Museum, just north of Central Saigon (District 1). There's a big 1975 section on the fall of Saigon, complete with scale models, maps with lights indicating strategic campaign points, and data on the American imperialist aggressors and their southern puppets. The Vietcong infiltrated the capital well before the final attack, dressed in Saigon Army uniforms. They stayed in Cholon, where the Chinese-always shrewd businesspeople-were already manufacturing North Vietnamese flags. The real Saigon Army soldiers stripped off their uniforms and fled, leaving mounds of clothing, 5 boots, and weapons on the streets. Others dressed in Vietcong-style black pajamas.

Apart from its centerpiece battle-plan model, the museum displays photos and small arms. Most signs are in Vietnamese, with scattered I English captions. Although the museum covers some events from 1945 on, most cover the period from 1973 to 1975, including a garbled 15 minute video on campaigns of that era. Some pictures document the use of bicycles, which were very important to the military success of the North Vietnamese. They moved tons of sup, plies along the Ho Chi Minh Trail in caravans of modified and reinforced bicycles. These "steel horses" could each carry up to 200 kilos of supplies, even through deep mud. If the Americans bombed a bridge, NVA troops simply ferried their bicycles across and carried on.

In the museum's outer courtyard lie rusting leftover hardware-a jeep, 85mm guns, small planes. There's an incongruous bonsai nursery and an art gallery-regular art downstairs, revolutionary art upstairs. For $500 you can buy a canvas showing the Fall of Saigon; for $200, a Cu Chi Tunnels painting. The Military Museum is open 0830-1130 and 1330-1600, closed Monday; entry is free.

Puppets

When the American imperialists left, their South Vietnamese puppets were crushed-sent to reeducation camps for the next six or seven years. But some puppets have never fallen out of favor with the North Vietnamese-water puppets. Right across the street from the Military Museum is the History Museum. Enter the grounds of the zoological gardens, $1; go into the History Museum, $1; then find the water puppet theater, another $2 for entry. The 20-minute shows are intended to delight children-but will please all ages. Shows start when the puppeteers ascertain the audience has enough kids-usually once an hour, on the hour. Small model water puppets are sold here, too. This is one of the few places you can see water puppets in Saigon (you can also see shows at the War Crimes Museum). There are special performances for children at festivals in other temporary sites, but no fixed venue as in Hanoi.

The History Museum is open daily 0800-1130 and 1330-1630, including Sundays and holidays. Interesting displays include the Cham sculpture section, with a superb standing bronze Buddha; the ethnography section, with displays of Central Highlands costumes and village models such as those from the Kontum-Pleiku area; a display of pieces from Funan, Oc-Eo, and Han Chinese periods; and the Buddha sculpture section, with superb Buddha and Avalokitesvara statues from East Asia. Under the French this 1928 structure was known as Musee Blanchard de la Brosse, set in what were once the finest French botanical gardens in Southeast Asia. Saigon's motley zoo collection has since been added to the flora, making this a zoological gardens-a relaxing place to pass time and chat with the locals. It's best to stick to the flora side; the animals look rather forlorn. Despite the ravages of war, the gardens present a great variety of plant species.

CHOLON PAGODAS

In 1978 the government launched an assault on capitalist practices in Saigon, primarily targeting the wealthy Chinese business community in Cholon, the "Chinatown" of Saigon. The following year China engaged Vietnam in a vicious border war in the north, and a quarter of Vietnam's ethnic Chinese fled the country-the first of the "boat people." Most of the exodus was from Saigon and Cholon, where every shop and house was ransacked for valuables and gold and many Chinese stripped of their wealth. In the

BIG MARKET

Cholon means "Big Market," and the area is certainly bustling. Especially in District 5, windows display luxury goods imported from China and Thailand, and the boulevards are jam packed with commuters on brand-new motorcycles and cyclos loaded with goods. Riverside warehouses are piled high with dried fish and sacks of rice; outdoor markets are thronged with customers. The largest market in Cholon is Binh Tay Market, off Hau Giang Boulevard in District 6. A courtyard-type block contains open-air and covered stalls, mainly in wholesale trade. The market is vast and colorful and sells everything from spices to silk; an ideal place to ramble for an hour or two. On the south side, there are many food stalls.

An Duong Market opened in late 1991 near the intersection of An Duong Vuong Boulevard and Su Van Hanh Street in District 5. This market shows the confidence of the Chinese community in the new Cholon-it was built with a $5 million investment from almost a hundred Cholon businessmen. The five-story market complex has 24,000 square meters of commercial space. The top two floors comprise a Taiwanese hotel and office complex; the lower floors offer retail space, with the first floor for clothing. The basement houses many small restaurants-a good place to dine on a budget.

1980s Cholon was a ghost town. Cautiously, ethnic Chinese have been returning since the normalization of relations with China in 1991 and the relaxation of foreign investment laws. Now it appears Cholon is once again becoming the economic powerhouse of the city, with high rents, thriving hotels, nightclubs, and department stores in District 5. The vice of gambling is back, too: Saigon Race Track in District 11 reopened in 1989; horse races are held four times a week.

The pagodas of Cholon once served as congregation halls for different Chinese communities depending on their origins-Fukienese, Cantonese, and so on. The communities fragmented in the 1970s and 1980s, and most pagodas were abandoned or fell into disrepair. Nevertheless, Cholon's pagodas are the finest in Ho Chi Minh City. A few have been restored, are active, and serve as showpieces for tourism. Other pagodas have been transformed-one has been turned into a local sports club, with weight lifting and bodybuilding hardware.

Quan Am Pagoda |

Quan Am Pagoda

Quan Am Pagoda, at 12 Lao Tu Street, is the most active pagoda in Cholon. Hawkers here sell incense sticks, paper offerings, and captive birds to a steady stream of devotees. About 25 nuns and monks are based at the temple, and several live on the premises. In front of the main altar is a white ceramic statue of Quan Am, known in Chinese as Guanyin, the Goddess of Mercy. There are also red wedding dresses and elaborate funeral chariots on display. The roof is richly decorated, with Chinese legends rendered in ceramic tiles.

Clear your lungs of incense and walk south toward the Phoenix Hotel. In the distance you'll spot a yellow building; the post office. It bears a Buu Dien sign, but you can still make out the old French PTT sign. In the open area I before the post office is a statue of Dinh I Phung, a Vietnamese hero famed for fighting I the French.

Pleasure City I

At a disused pagoda on a corner, turn onto tiny Phu Dinh Street, a tiny neighborhood street with old architecture and lots of local cafes. Halfway along, at number 7, is the house seen in the French movie The Lover. It is now a small cafe (you can get a better idea of the original architecture by looking at number 9 or number 15). The Chinese shop house looks rather bland and innocent now, difficult to imagine as a trysting place in a steamy affair between a Chinese man and a French schoolgirl. But remember the context: Cholon in the 1930s, '40s, and '50s was rife with opium dens, mahjong joints, and gambling joints like the Grand Monde Casino.

In 1957, French adventurer Gontran de Poncins wrote: "Cholon is the Chinese pleasure city. Cholon is the night city with electric signs in Chinese characters that gleam like rubies and taxi girls whose shapely bodies stir the customers... Cholon is the gambling city... the city of opium dives where, for a few piastres, you can have a flap-board bed, a nugget of opium, a boy to prepare your pipes and, if you so wish, a companion to lie beside you. Cholon is open to all desires!" Cholon had a reputation as a place for business and pleasure, often conducted in the same hotel. The City of Pleasure appears to be reviving, with seedy karaoke, nightclubs, and taxi dancers in major hotels catering to Asian businessmen.

Goddesses and Generals

Thien Hau Pagoda, at 710 Nguyen Trai, honors Thien Hau, the goddess of the sea, and protectress of sailors and fisherfolk. Thien Hau also retains elements of the Taoist Queen of Heaven, and is a popular deity in Hong Kong and Taiwan. The pagoda was constructed in the early 19th century and is one of the largest and busiest in the city. It was once the focus of the Cantonese community. Recently restored, it now serves as a showpiece for Saigon Tourism. Inside the front gate are two enormous incense urns; huge incense spirals burn for hours. The principal temple image is a gilded Thien Hau; a model boat lies nearby. More interesting visually are the intricate ceramic friezes on the temple roof, best viewed from a small courtyard. Opposite the temple is a run-down old fishpond, formerly connected with temple ceremonies. Although Thien Hau Pagoda is busy all day, there are special services on Sunday at 0600 and 1600.

One block to the east is Nghia An Hoi Quan Pagoda, at 678 Nguyen Trai. The temple was built by the Chaozhou Chinese congregation. After passing a carved wooden boat shading the entrance, you come to the larger-than-life red horse of Quan Cong, a revered Chinese general. The statue of Quan Cong is encased in glass and bears a red face, long beard, and green costume. He's flanked by two assistants, a general and a mandarin.

Continue to Tam Son Hoi Quan Pagoda, at 118 Trieu Quang Phuc Street, a Fukienese pagoda that has fallen into neglect. It's dedicated to Me Sanh, Goddess of Fertility-childless mothers patronize a statue at the back. The temple was built in the 19th century in Sino-Vietnamese style and is pleasantly uncluttered.

SAIGON PAGODAS

Saigon has upwards of 200 pagodas. Most are either run-down or humdrum; the best are found in Cholon. A pagoda is a community center of sorts and often a repository for small funerary jars, each containing the ashes of the deceased with a photo and nameplate. Newer pagodas, such as Xa Loi and Vinh Nghiem, are of more interest at festival time, when they're ablaze with incense and thronged with devotees and beggars. Some of the following pagodas are located on the fringes of Saigon.

You'll find the small Jade Emperor Pagoda at 73 Mai Thi Luu Street, off Dien Bien Phu Street. Built in 1900, it's home to a bizarre collection of carved wood deities-some Buddhist, some Taoist. Presiding at the main altar is Ngoc Hoang, the Taoist Emperor of Jade. The wooden panels in a side chapel, the Hall of the Ten Hells, show the thousand tortures awaiting evildoers. Near the main entrance, to one side of the temple, a chamber holds many small ceramic figures of mothers and children cloaked in red-a fertility shrine of sorts, visited by women.

Dai Giac Pagoda is located at 112 Nguyen Van Troi, near Saigon Omni Hotel. Dai Giac is

cluttered with kitsch-more like a Chinese amusement park than a pagoda. Inside are Buddha and Quan Am statues in glass cases, a few lion statues, a magnificent brass gong, a huge black drum made of porcelain with mother of pearl inlay, and funerary urns bearing photos of the departed. In the courtyard is a huge Laughing Buddha made of wood, and a grotto with a Quan Am statue. To the north side of Dai Giac a six level pagoda features an exterior coated in pieces of broken porcelain; linked to the pagoda are monks' quarters.

Vinh Nghiem Pagoda is also on Nguyen Van Troi, just south of Thi Nghe Channel. Here there are two buildings-the main temple and a seven-story pagoda. The latter contains funeral urns, and is open only on holidays and at festival time, when the place is packed. The temple was completed in the early 1970s with assistance from the Japan-Vietnam Friendship Association, which explains the Japanese architecture. The interior walls hear scrolls with scenes from the Jataka Tales. The temple's large bell was a gift from Japanese Buddhists, presented during the Vietnam War.

Xa Loi Pagoda, at 89 Ba Huyen Quan Thanh Street off Dien Bien Phu Street in District 3, is a large modern concrete structure with a large, newish Buddha backed by a neon halo. In the courtyard below is a stucco Quan Am. Xa Loi was the headquarters of militant Buddhists during their struggle to overthrow the Diem regime. In August 1963 thousands demonstrated to protest religious persecution; on August 21 special forces attacked the pagoda, and martial law was declared.

Thich Quang Duc Shrine is named for a 66year-old monk from Hue who immolated himself on June 11, 1963. A photograph of the monk in flames made front-page news around the world. Some 30 monks and nuns followed his example, protesting the Diem regime and U.S. involvement in Vietnam. Diem's sister-in-law Madame Nhu made jokes about barbecued monks and said, "Let them burn-we shall clap our hands!" This shrine lies at the corner of Nguyen Dinh Chieu and Cach Mang Thang Tam Streets, a few blocks south of Xa Loi Pagoda. The car used to drive the monk to the immolation site is in Thien Mu Pagoda in Hue.

On the outskirts of Saigon in District 11, the Vietnamese-style Giac Vien Tu Pagoda is dedicated to Emperor Gia Long. The accumulation of 300 years of incense burning imbues this place with a striking atmosphere. There is a profusion of carvings-Buddhist, Taoist, and Confucian deities and mythical figures. The most significant is a large gilded statue of Amitabha, Buddha of the Past. After a body is cremated, the ashes are transported in a funeral carriage to the pagoda. Numerous funerary jars are on view in the first chamber. Twenty monks are attached to the temple, and half live on the premises. The temple is hard to find-it's about 200 meters off Lac Long Quan Street. Get there by moto or rental car.

Giac Lam Pagoda, at 118 Lac Long Quan Street in Tan Binh District, was built in 1744. It is believed to be the oldest pagoda still standing in Saigon. It's quite similar in architecture and atmosphere to Giac Vien Tu Pagoda. The two pagodas are a few kilometers apart; a visit to one or the other should suffice. Giac Lam is large, and has darkened halls with carved jackwood statues. Senior monks wear yellow robes; novice monks wear brown robes.

Other Sights

War Tourism at Cu Chi |

Cu Chi Tunnels

Some people love it, others find it kitschy, and worse. With fabricated props and posed mannequins, is this what War tourism looks like? Still, the bus loads of tourists make the trip. If you're deciding to go, consider how much time you have in Saigon. If it's limited, this half-day trip should not detract from sightseeing in Saigon. The drive out is not too interesting, in the thick of traffic with little scenery, and the site is crawling with tourists. However, we'll pack you a delicious picnic lunch and will make the trip unique. If you go, bring earplugs, automatic rifles may be fired at the site and are deafening. Read more about visiting the Cu Chi Tunnels.

Additional Museums

The Art Museum (Bao Tang My Thuat), in a mansion at 97A Pho Due Chinh Street in central Saigon, displays revolutionary art and sculpture, as well as artifacts from the Oc-Eo civilization.

The Ho Chi Minh Museum occupies the old French customs house, known as Dragon House Wharf, at the confluence of the Saigon River and Ben Nghe Channel. The French transport company Messageries Maritimes once had its headquarters here. The museum celebrates the exploits of Uncle Ho, who left Saigon at the age of 21 aboard a French freighter from this wharf.

Signing on as a galley boy, he departed in 1911 on an extended journey through Europe, Africa, North America, and Asia and did not return to Vietnam until 1941. A visit to the museum is compulsory for legions of Saigon schoolchildren, who have their photos taken with a statue of Uncle Ho in the background.

Museums in Ho Chi Minh City are usually open Tuesday-Sunday 0800-1130 and1400-1700.

Reunification Hall

Reunification Hall, or Thong Nhat Conference Hall, is one of those take-it-or-leave-it destinations. Some like it, some hate it. On entry you get a brochure; there's also a crackly revolutionary film thrown in along the line. A cross between a museum and conference center, the rambling Reunification Hall exudes a sterile atmosphere and displays appalling taste in architecture and furnishing. Sometimes the place is closed for state occasions; otherwise, it's open 0730-1030 and 1300-1600 daily. There are two entrances and exits: the main gates are on Nam Ky Khoi Nghia; there is a side entrance on the south side of the grounds at 106 Nguyen Du Street. Visitors must take a guided tour; the English of the guides may be poor.

The Hall was formerly the site of Norodom Palace, the residence of the French Governor general of Indochina, built in 1868. The Governor-general spent little time there as his principal seat was in Hanoi. After the Geneva Conference in 1954 and the installation of President Ngo Dinh Diem, the place was renamed the Presidential Palace. In 1962, two South Vietnamese Air Force pilots turned their firepower on the palace in an attempt to assassinate Diem. The president and his family escaped to the cellar, but the palace was largely destroyed. Diem had the place razed and ordered construction of a new palace (which he did not live to see through due to his assassination in December 1963).

The present building was thrown up in the early 1960s-designed by Paris-trained architect Ngo Viet Thu, who combined Western and Oriental architectural elements within a Chinese structural framework. On October 31, 1966, the Thieu-Ky administration inaugurated the new presidential palace. Thieu lived and worked there for the next eight years. In early April 1975 another renegade pilot bombed the new palace, damaging part of it. On April 30, 1975, NVA tanks smashed down the gates of the palace. The NVA took control of Saigon, arresting President General Duong Van Minh and his cabinet. A short career for General Minh: he'd become head of state only two days before. After a period of reeducation, Minh was allowed to emigrate to France in 1983.

The hall has been preserved as it was on April 30, 1975. Various rooms are decorated with lacquered paintings and filled with dowdy 1960s furniture. More interesting are the basement and the rooftop. President Nguyen Van Thieu had a bombproof bunker built in the basement of the Hall; from here he conducted government affairs until April 1975, when he fled. The bunker was the nerve center for conducting the war: you can view military maps, field radios, and banks of U.S. telecom gizmos. The President's Mercedes is parked near the kitchen. On the rooftop is a helipad with a Huey helicopter parked on it. This makes a macabre photo-op: group tours are sometimes permitted to line up for pictures, pretending it's 1975 and they're scrambling for the last chopper out. In this area is a small coffee shop, and a video salon with a longish scratchy documentary with excerpts from a French television documentary. The video shows events leading up to the fall of Saigon-from the Vietnamese Communist point-of-view, of course.

Parked on the manicured grounds of Reunification Hall are some stray bits of hardware from the war. Near the main gate is a Soviet tank supposedly the one that smashed down the same gate on April 30, 1975, although there seem to be an awful lot of tanks around laying claim to this honor. It appears that at least two NVA tanks smashed down the gates. Tank 843 rammed the side gate, and Tank 390 crashed through the front gate (the commander of Tank 843 raced up to the fourth floor balcony to grab the main trophy-which was the South Vietnamese flag). Parked on the northeast side of the grounds is an American F-5E jet that was flown by South Vietnamese pilot Nguyen Thanh Trung. On April 8, 1975, double-agent Nguyen made a radical departure from his scheduled bombing run: he suddenly banked and left his squadron's formation in midair, turned back-and dropped two bombs on the palace before defecting northward.

Hindu and Muslim Temples

Saigon's eclectic mix of temples includes a few mosques and Hindu temples. Like the ethnic Chinese, Hindus and Muslims were persecuted by the revolutionary government and most, including the spiritual leaders, fled Vietnam. Still, there are a dozen mosques around Saigon. At 66 Dong Du Street, off Dong Khoi, is Saigon Central Mosque, built by South Indian Muslims in 1935. The spotless blue and white structure features four minarets and is a tranquil retreat in the heart of the city; excellent Indian food is served at lunch hour.

Within a few blocks of Ben Thanh Market stand two Hindu temples. To the northwest of the market is Mariamman Temple, at 45 Truong Dinh Street. This century-old site is dedicated to the goddess Mariamman; it was taken over in 1975 and turned into a joss-stick factory. To the northeast of Ben Thanh Market is Pani Hindu Temple (also called Sri Thenday Litthapani), at 66 Ton That Thiep. This temple-over a century old-was disbanded after 1975, but in early 1993 the government returned the temple to Saigon's tiny Hindu community. Hindu adherents of several nationalities come to this sacred shrine. You enter through a colonnaded interior courtyard with a small shrine guarded by horse statues, and an ornate door with bells mounted on it. If the walls look bare, it's because a lot of the statuary went missing-the central statue has been replaced by a picture. Framed pictures of Indian deities and important figures grace the walls-Shiva, Vishnu, Ghandi, Nehru. On the roof are towers with detailed Hindu sculpture.

Saigon Dining

Saigon features the finest restaurants in the country, from busy street and alley soup stalls with small plastic chairs Bourdain loved, that look as if they've been there for decades, to newer fusion places opened by returning Vietnamese (Viet Kieu) such as chef Luke Nguyen and his elegant Vietnam House restaurant. Cuisine is always a primary focus of our trips, and in Vietnam, rightly so. We'll make sure you dine well no matter what city, style or type of meal you're desiring. We can also blend in cooking activities, such as shopping and cooking demonstrations with local chefs. Below are a few recommended places for dinner in Saigon.

Hoi An Sense - 11 Le Thanh Tong Street, District 1

Already missing Hoi An? The Restaurant was created and designed with the architectural themes of the ancient towns of Hoi An and Imperial Hue. The food follows on the design, with delicately carved vegetables, colorful combinations and beautiful presentation all contributing their part to the traditional Imperial styles dishes.

Hoa Tuc - 74 Hai Ba Trung Street, District 1

Hoa Tuc though a modern, sophisticated Vietnamese restaurant is located in an old alleyway that also contains several other well-regarded additions to the international dining scene in Saigon. The restaurant is beautifully decorated, comfortable and clean with excellent service, including how to best construct your rice paper rolls.

CucGach Quan, 10 Dang Tat Street, Tan Dinh Ward, District 1

Cuc Gach Quan or " brick restaurant" is located at the edge of District 1 and Phu Nhuan District in a lovely converted French villa. With a pleasant ambiance and decor you'll experience tasty traditional favorites served in old-style clay pots, with china and wooden tables resembling a countryside kitchen.

TIB - 187 Hai Ba Trung Street, District 1

A finer restaurant specializing in the cuisine of Hue with traditional decor serving Hue specialties, including chicken with lemongrass, BBQ pork rice paper rolls, and banh xeo (Vietnamese crepe).

Temple Club - 29 & 31 Ton That Nghiep Street, 1st floor, District 1

The Temple Club is also located in a beautiful restored French villa in the busy Dong Khoi area. An elegant setting and impeccable service compliments fine Vietnamese dishes.

Saigon Hotels

See standout properties in Vietnam, including Ho Chi Minh City (Saigon)

When to go

Saigon is warm and sunny year-round, though the monsoon brings have, intermittent daily showers in the afternoon from July through September (and high humidity).