Japan's Culinary Obsession

Nowhere is the mantra "food is culture" truer than in Japan. Indeed, over the last decade Japan has quietly become one of the top culinary destinations in the world and even, arguably, the best of all. And no small wonder why. Here you’ll find the greatest breadth of tradition, quality, and variety, of any place in the world. Every city has its own delicacies, each district something unique, and each region a distinctive style. Let us explore you to the country's cuisine top to bottom—from sizzling street food, local bistros, renowned sushi bars, and to some of the finest Michelin-recognized restaurants in world.

Evolution of Japanese Cuisine

Japanese cuisine is ubiquitous, everyone has a favorite sushi bar and are certainly familiar with other favorite Japanese exports such as tempura and ramen. But how much do we really know about Japan's complex culinary tradition? We know it’s typically healthy, fresh, and it tastes wonderful, and for many of us, that’s all we need to know. Like many countries in the region, the cultivation and preparation of rice has always played a central role in Japanese food culture. providing an abundant staple for an emerging civilization. The rice-centered food culture of Japan evolved rather recently, following the adoption of wet rice cultivation learned from other parts of Asia slightly more than 2,000 years ago. Centuries following the introduction of Buddhism to Japan in the 6th century, laws and imperial edicts gradually eliminated the eating of almost all flesh of animals and fowl. The vegetarian style of cooking known as shojin ryori was later popularized by the Zen sect, and by the 15th century many of the foods and food ingredients eaten by Japanese today had already made their debut, for example, soy sauce (shoyu), miso, tofu, and other products made from soybeans. The Japanese tradition of rice served with seasonal vegetables, fish and other seafood reached closer to the highly sophisticated form we know of today during the Edo period from 1600 to 1868.

During this time, a highly formal and elaborate style of cooking developed that was derived from the style used within the court aristocracy—honzen ryori, now one of the three basic styles of Japanese cooking along with chakaiseki ryori (the cuisine of the tea ceremony meal) and less formal, kaiseki ryori. Enjoying the old and welcoming the new Honzen ryori An example of this formalized cuisine, which is served on legged trays called honzen.

With an emphasis on the artistic presentation of fresh, seasonal ingredients, the tea meal married the formalities of honzen ryori to the spirit and frugality of Zen. Kaiseki ryori developed in its present form in the early 19th century and is still served at first-class Japanese restaurants known as ryotei and at traditional Japanese inns. While retaining the fresh seasonal ingredients and artful presentation of earlier styles, kaiseki meals have fewer rules of etiquette and a more relaxed atmosphere. Sake is drunk during the meal, and, because the Japanese do not generally eat rice while drinking sake, rice is served at the end. Appetizers, sashimi (sliced raw fish), suimono (clear soup), yakimono (grilled foods), mushimono (steamed foods), nimono (simmered foods), and aemono (dressed salad-like foods) are served first, followed by miso soup, tsukemono (pickles), rice, Japanese sweets, and fruit. Tea concludes the meal. Although most Japanese people have few opportunities to experience full-scale kaiseki dinners, the types and order of foods served in kaiseki ryori are the basis for the contemporary full-course Japanese meal.

The sushi that most people are familiar with today—vinegared rice topped or combined with such items as raw fish and shellfish—developed in Edo (now Tokyo) in the early 19th century. The sushi of that period was sold from stalls as a snack food, and those ancient stalls were the precursors of today’s sushi restaurants. Not many people realize, American sushi has evolved from Japanese.

Regardless of traditions, in the 150 or so years since Japan reopened to the West, Japan has developed an incredibly rich and varied food culture outside of native-Japanese cuisine with many foreign dishes, some adapted to Japanese tastes while others remain less unchanged.

Japan’s first substantial and direct exposure to the West came with the arrival of European missionaries in the second half of the 16th century. At that time, the combination of Spanish and Portuguese game frying techniques with a Chinese method for cooking vegetables in oil led to the development of tempura , the popular Japanese dish in which seafood and many different types of vegetables are coated with batter and deep fried. With the reopening of Japan to the West in the mid-19th century, many new cooking and eating customs were introduced, the most important being the eating of meat. Although now considered a Japanese dish, sukiyaki—beef, vegetables, tofu, and other ingredients cooked at the table in a broth of soy sauce, mirin (sweet sake), and sugar—was at first served in “Western-style” restaurants. Another popular native dish developed in this period is tonkatsu, deep-fried breaded pork cutlets. Created in the early 20th century using Indian curry powder imported by way of England, kareraisu—curry rice—became a very popular dish, made with vegetables and meat or seafood in a thick curry sauce that is served over rice.

Contemporary Japanese Cuisine

Even with easy access to global styles, native Japanese food is still the norm, and a “Japanese meal” at home will generally feature white rice, miso soup, and tsukemono pickles. The multiple dishes that accompany these three vary widely depending on the region, the season, and family preferences, but candidates include cooked vegetables, tofu, grilled fish, sashimi, and beef, pork, and chicken cooked in a variety of ways. Japan’s most famous contribution to global food culture—sushi—is generally eaten at sushi restaurants where customers sit at the counter and call out their orders item by item to a sushi chef. There are also very popular chains of “conveyer-belt” sushi restaurants where you simply pull small plates of sushi off the rotating conveyor belt passing by you.

Unlike Japanese restaurants abroad, which often serve a range of different types of Japanese food, restaurants in Japan generally specialize in a single type, such as sushi, tempura, shabushabu (thin slices of beef cooked at the table by dipping into a simmering broth), sukiyaki, unagi (grilled eel), soba and udon noodles, etc. The main exceptions to the specialization rule are the chains of family restaurants, which usually serve a range of Japanese, Western, and Chinese dishes. (See descriptions of both below).

Unlike Japanese restaurants abroad, which often serve a range of different types of Japanese food, restaurants in Japan generally specialize in a single type, such as sushi, tempura, shabushabu (thin slices of beef cooked at the table by dipping into a simmering broth), sukiyaki, unagi (grilled eel), soba and udon noodles, etc. The main exceptions to the specialization rule are the chains of family restaurants, which usually serve a range of Japanese, Western, and Chinese dishes. (See descriptions of both below).

Two types of restaurants which are found in large numbers all over Japan but which are not considered native to Japanese are ramen and yakiniku restaurants. Ramen restaurants, unlike the simple packages bought in stores, serve large amounts of Chinese-style ramen noodles in big bowls with delicious broth (flavored with soy sauce, miso, salt, etc.), roast-pork slices, and various vegetables (bean sprouts, scallions, etc.), and many people also order gyoza (Chinese dumplings) to accompany their ramen. At yakiniku restaurants, which are based on Korean style barbecue, guests cook bite-sized pieces of beef, other meats, and vegetables over a charcoal or gas grill at the table. Most large cities also have a considerable number of other foreign-food restaurants serving French, Italian, Indian, Chinese, Korean, and other cuisine, and in Tokyo an almost unlimited selection of the world’s food is available.

At the opposite end of the price spectrum from elegant kaiseki ryotei and French restaurants are the food stalls that are still a familiar sight in some urban districts and at festivals and other outside events where many people gather. Some of the most popular stalls are those serving yakisoba (fried soba noodles), yakitori (grilled chicken pieces on a skewer), okonomiyaki (pancakes with vegetables and a variety of other ingredients), frankfurters, and buttered baked potatoes.

Ingredients of Japanese Cooking

What am I tasting? Your dishes typically has some of these staples used in Japanese cooking:

- Japonica, short-grain white rice. The staple of all Japanese cooking.

- Japanese soy sauce. Since soy sauces produced by various soy-sauce-using countries differ. Japanese soy sauce, rather than Chinese, or others is used.

- White miso (shiromiso). There are different kinds of miso, but the white (actually a pale yellow-brown) variety is the most versatile and common.

- Bonito flakes (katsuo bushi). Not only is this used to make dashi stock, but it's also used as a condiment in so many foods such as tofu, blanced spinach, and such. A purist can get a solid dried bonito and shave their own, but the pre-shaved bags are more convenient.

- Konbu seaweed. Essential for making good dashi stock, as are bonito flakes.

- Sake. In a pinch, a sweet sherry can be substituted, but many Japanese foods include sake as an ingredient.

- Mirin is sweet fortified liquor made from rice, used exclusively in cooking, most recognizable as the sauce used with yakatori.

- Rice vinegar. Rice vinegar is mild and sweeter than white wine vinegar.

- Dried shiitake mushrooms. More intense in flavor than fresh, they are used a lot for flavoring or as an ingredient.

- Sesame seeds. These are often used toasted and ground up, or whole as a condiment.

- Dark sesame oil. Used for flavoring many dishes, especially chuuka (Japanese Chinese-style) dishes.

- Tofu and tofu products such as aburaage (fried thin tofu), atsuage (tofu blocks that have been deep fried), kohya dofu (frozen and dried tofu, somewhat spongy), okara and yuba (very thin sheets of dried tofu).

- Green tea leaves. Sencha is the standard green tea (shincha is new sencha), and there is kukicha (made from the stems), genmaicha (with toasted rice), hatomugicha (with toasted barley), and so on. Matcha, or powdered green tea, is not made that much in the home (you get it at tea ceremonies, prepared by a skilled person), but it's often used nowadays for cold drinks and ice cream.

- Non-Japanese dry or bottled ingredients that are often used in Japanese cooking: salt, sugar, Worcestershire sauce, mayonnaise, potato starch flour or cornstarch flour, and white wheat flour.

- Fresh ginger. Powdered ginger cannot be substituted!

- Nori seaweed. The black dried sheets used to wrap sushi rolls, also used shredded as a topping and so on. It's even cooked to a paste to eat with rice.

- Wakame seaweed. This is available either preserved in salt, or dried. The dried kind is easier to handle. Used in miso soup, salads, and as sashimi garnish.

- Spring onions or green onions and leeks. Leeks are used more than onions, though onions are used in a lot of Japanese Western-style dishes (yohshoku) such as omurice (omelette and rice)

- White daikon radish. In Europe, mouli can be substituted. Used cooked as well as raw; in stews, soups, as garnish, etc. Grated daikon radish cuts down on the oiliness of things like tempura and grilled oily fish. In a pinch a chef will use red radishes instead, especially for salads, grating and so on.

- Wasabi ("Japanese horsehradish") paste or powder.

- Ground curry powder—very popular in Japan.

—Makiko Itoh (Just Hungry)

Styles, Dishes and Themes of Japanese Cuisine Defined and Explained

Agedashi dōfu

Agedashidofu is made of lightly breaded tofu which is then fried and served hot in a dashi soy sauce broth and commonly garnished with green onions or grated daikon. Tasty small bowls of agedashi dōfu can be found in a variety of restaurants and is common izakaya food (casual places for salaryman after-work drinking).

Sushi (Japanese style)

Sushi needs no introduction, although interestingly enough the original type of sushi, known today as nare-zushi, was first made in Southeast Asia, possibly along what is now known as the Mekong River, and the contemporary version we recognize, internationally known as "sushi", can actually be traced to an inventor, Hanaya Yohei (1799–1858), from the end of the Edo period in Edo. Learn about the various styles of sushi below, although most sushi we enjoy is typically Makizushi (rolled sushi) and Nigirizushi (Nigiri) or rice with protein on top. Note sashimi is not considered sushi, as it is not made with rice.

Types of sushi include:

Chirashizushi

ちらし寿司 or"scattered sushi" is a bowl of sushi rice topped with a variety of raw fish and vegetables/garnishes (also refers to barazushi) and often cooked for celebrating special occasions, including festivals.

Inari Sushi (Inarizushi)

稲荷寿司 does not resemble sushi, but is a pouch of salty deep-fried tofu typically filled with sushi rice alone. This simple vegetarian- and vegan-friendly form of sushi is perfect for a snack, a picnic lunch, or as part of your sushi dinner platter.

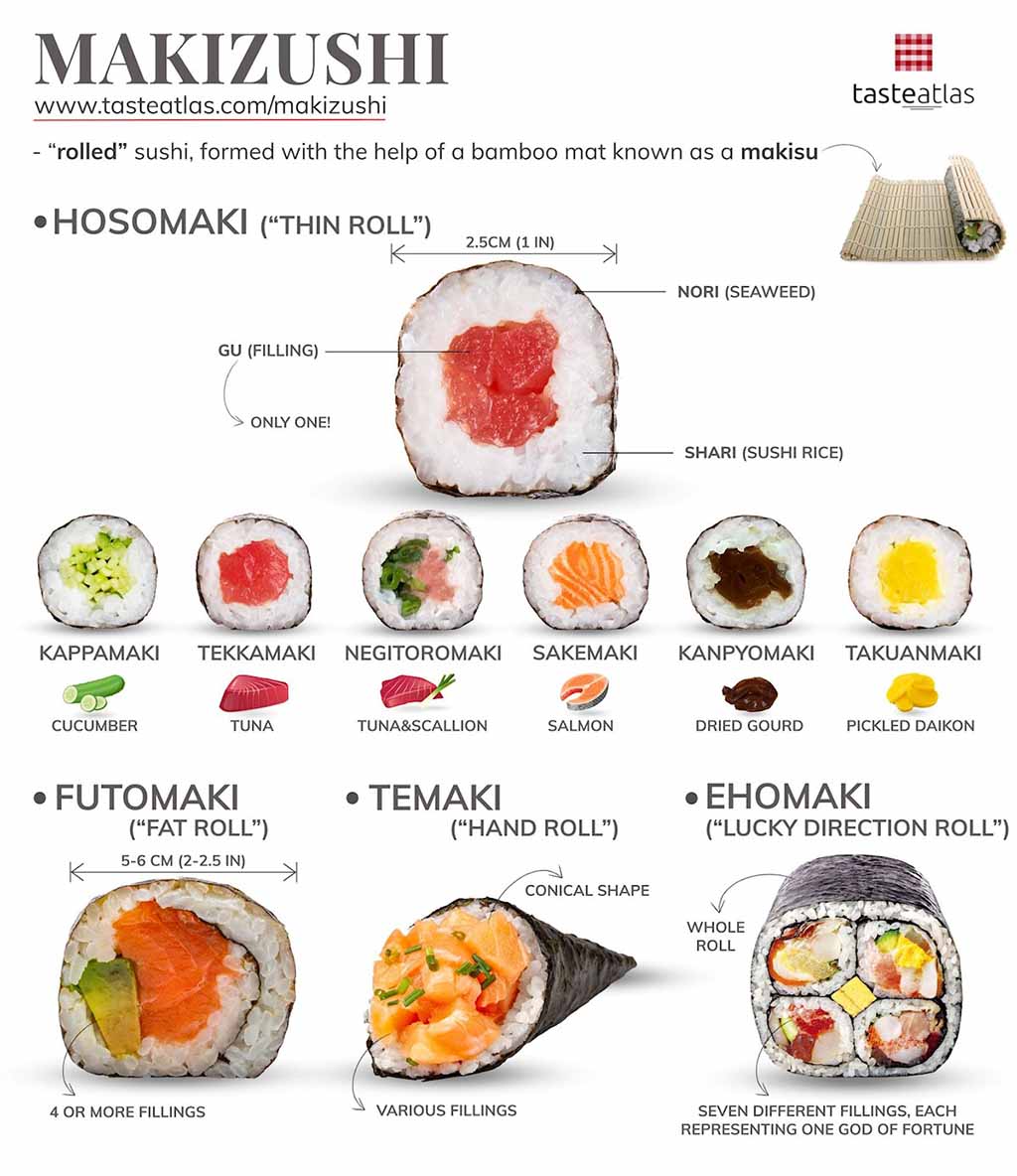

Makizushi

巻き寿司, "rolled sushi", norimaki (海苔巻き, "Nori roll") or makimono (巻物, "variety of rolls") is the most recognizable form of sushi, a cylindrical piece, formed with the help of a bamboo mat known as a makisu (巻簾).

Makizushi by Taste Atlas

Futomaki

太巻, "thick, large or fat rolls" is a larger round piece like Makiushi, usually with nori on the outside but bigger in size that usually contains anywhere from four to ten or more different ingredients. Futomaki is Kansai dish that originated as a festival food, but is now popular throughout Japan.

Hosomaki

細巻, "thin rolls" are the most popular of the makizushi varieties. The most common are the tekkamaki tuna roll and the light kappamaki cucumber roll.

Temaki

手巻, "hand roll" is a large cone-shaped piece resembling an ice cream cone, of nori on the outside and the ingredients spilling out the wide end. Made with the usual sushi ingredients—rice, raw fish, and vegetables wrapped in a piece of nori seaweed. A simple dish to make, temaki is most commonly made at home and not in sushi restaurants.

Narezushi

熟れ寿司, "matured sushi" is a traditional form of fermented sushi believed to be the earliest form of sushi to appear in Japan and noted in 10th century texts, thought that this combination of fish pickled with rice and salt was a way to preserve fish. The most popular narezushi is from the Shiga Prefecture and is called funazushi, prepared with carp (nigorobuna) from Lake Biwa. The dish is time-consuming to make and is considered a delicacy.

Nigirizushi (Nigiri)

握り寿司, or "hand-pressed sushi" is another very common form of sushi developed in Tokyo during the 1800s. It is most recognizable to non-Japanese along with makizushi (suchi rolls), formed of an oblong mound of sushi rice that the chef presses into a small rectangular square between the palms of the hands, usually with a bit of wasabi, and a topping (the neta) draped over it. Note that in Japan, nigiri is eaten as is (and not adding wasabi and certainly not soy sauce, as your chef has prepared it ready to eat). Eat nigiri whole, with your fingers. If you are taking a sushi making class during your time in Tokyo (highly recommended), this is the type of sushi you will be creating along with makizushi (above)

Gunkanmaki

軍艦巻, "warship roll" is a special type of nigirizushi: an oval, hand-formed clump of sushi rice that has a strip of nori wrapped around its perimeter to form a vessel that is filled with some soft, loose or fine-chopped ingredient that requires the confinement of nori such as roe, nattō, oysters, uni (sea urchin roe), corn with mayonnaise, scallops, and quail eggs. Gunkanmaki originated in 1941 at Kyubey, a small sushi shop located in Tokyo’s Ginza that has since earned its name as one of the top sushi restaurants in the world.

Oshizushi

押し寿, "pressed sushi", also known as hako-zushi, "box sushi", is a large single-piece of pressed sushi from the Kansai region, and also a favorite and specialty of Osaka. Traditionally, it includes marinated or grilled seafood including eel or mackerel, but the varieties which employ raw fish are also quite common. The unique preparation method allows the creation of very complex versions of oshizushi, which may consist of many layers or may have detailed and comprehensive creations on top of each individual piece. For its ease of portability, it is a popular take away item.

Uramaki (California Roll)

The ubiquitous "inside-out roll" is a medium-sized cylindrical piece with two or more fillings with a method originally meant to hide the nori. Uramaki differs from othermakimono because the rice is on the outside and the nori inside. This sushi roll is prepared with sushi rice, nori, crab or surimi, avocado, and cucumber.

United States-style Makizushi. Futomaki

A a more popular variation of sushi within the United States, and comes in variations that take their names from their state of origin. Other rolls may include pretty much anything, including chopped scallops, spicy tuna, beef or chicken teriyaki roll, okra, and assorted vegetables such as cucumber and avocado, and the "tempura roll", where shrimp tempura is inside the roll or the entire roll is battered and fried tempura-style.

Other Popular Japanese Dishes

Bento

Chains of shops sell a variety of popular Japanese box lunches known as bento, recognizable to most westerners. The English name “box lunch” notwithstanding, bento are often eaten for dinner as well. Many shops are takeout only, but some have tables available for informal dining.

Chawanmushi (savory egg custard)

Chawanmushi (savory egg custard)

"Chawan mushi is one of those Japanese dishes I've enjoyed in restaurants for years but always thought would be too hard to make at home. A steamed savory custard served in an cup, chawan mushi is made from eggs, dashi and soy sauce, usually with tasty tidbits added like ginko nuts, shrimp, chicken or thin slices of reconstituted dried shiitake mushrooms. When wife Momo decided to make chawan mushi, sans the tidbits, for baby Gen -- who basically loves every food that hits his lips -- I realized that this dish was totally doable in a home kitchen; easy, in fact. But, surprise, surprise, baby Gen didn't like Momo's chawan mushi! I did, though, and resolved to make it myself a few days later to understand the method. The keys are passing the egg mixture through a sieve and steaming for just the right amount of time. Here's the recipe, with chicken, shrimp and dried shiitake. Give it a shot!" (recipe) —The Japanese Food Report

Gyoza

Gyoza are dumplings stuffed with a filling made of minced vegetables and ground meat. Gyoza were introduced to Japan from China. Japanese gyoza are usually prepared by frying them, and they are commonly served as a side dish to ramen.

Jidohanbaiki (vending machines)

Jidohanbaiki, or simply, jihanki, are the ubiquitous vending machines found almost everywhere in Japanese cities and town, in stations, shops, and streets all over Japan (estimated to be roughly 5.5 million in number). Surprisngly, vending machines were imported in Japan all the way back at the beginning of the Meiji Era (1868 - 1912) from Western countries using similar devices (primarily for tobacco products). Locals use them every day as mostly a convenient way to purchase drinks, but jihanki offer all sorts of products, tickets, including tobacco, magazines, sweet snacks, rice, frozen foods, popcorn, noodle soups, and other quick meals to go. During your trip, you may also discover jihanki are the ideal way to grab a quick refreshment. Jihanki are coin-operated, though increasingly App/QR-code friendly (Acure Pass is the most popular).

Kare Raisu

Kare raisu (Curry Rice) is cooked rice with a Japanese curry sauce. It can be, and is typically, served with additional toppings such as tonkatsu (fried pork filet). Curry is not a native Japanese spice, but has now been used in Japan for over a century though it is much milder than Thai or Indian versions you may be familiar with. Kare Raisu is a very popular dish, and many inexpensive Kare Raisu restaurants can be found in most cities and towns, especially in and around train stations.

Okonomiyaki

A popular savory Japanese style pancake-like comfort food dish (also known as the Japanese pancake or the Japanese pizza). A convenient snack, okonomiyaki made from stands in parks or along streets. Styles of okonomiyaki vary quite a bit by location, with a simple okonomiyaki pancake (usually made with a batter of flour, eggs, and water) typically featuring add-ons including cabbage, meat, and seafood, and toppings include okonomiyaki sauce, aonori (seaweed), katsuobushi (fermented tuna flakes), Japanese mayonnaise, and pickled ginger. The two significantly different types of okonomiyaki are the Kansai, or Osaka style, in which all ingredients are all mixed into a batter and then grilled. The other is Hiroshima style, in which the pancake is grilled and then other ingredients are layered on top often with more cabbage. .

Hiroshima style okonomiyaki

Begin with a layer of the batter, poured onto the pan that is topped with a pile of shredded cabbage and bean sprouts and then some shrimp and bacon. Cook until the batter in golden brown, then flip and simmer until the bacon is crisp. By now some noodles are fried in a separate area and then topped with the rest of the okonomiyaki. Finally an egg is fried and the whole okonomiyaki is placed on top of it with the noodle side down. Serve with the egg side up and topped as you like. View a website devoted entirely to okonomiyaki: http://okonomiyakiworld.com

Ramen

Every college student has eaten dehydrated and packaged instant ramen in the form of Cup of Soup, the world's most popular quick meal but the low-cost Chinese-noodle dish is practically a religion in Japan, a staple dish for all Japanese. Every region in Japan has its own variation of ramen, such as the tonkotsu (pork bone broth) ramen from Kyushu and miso ramen of Hokkaido.

After World War II, cheap flour imported from the United States swept the Japanese market while at the same time, millions of Japanese troops had returned from China and continental East Asia from their posts in the Second Sino-Japanese War. Many of these returnees had become familiar with Chinese cuisine and subsequently set up Chinese restaurants across Japan. In 1958, instant noodles were invented by Momofuku Ando, the Taiwanese-Japanese founder and chairman of Nissin Foods. Named the greatest Japanese invention of the 20th century in a Japanese poll, instant ramen allowed anyone to make this dish simply by adding boiling water (Wikipedia).

Tasty ramen is often served in the most casual of settings, such as from yatai (food carts) and there are also numerous and popular ramen chains, such as Ichiran (famous for their tonkotsu ramen), but also now Michelin-star ramen places (Tsuta Ramen). Fukuoka is famous for ramen, and the best tonkotsu in Japan, Shin Shin (シンシン) is one the best ramen shops in the city (lunch only).

Yakiniku

Yakiniku, literally "grilled meat", or overseas known as "Japanese barbecue," is recognizable from restaurants with table-top grills on which diners cook bite-sized pieces of beef, pork, other meat, and vegetables at the table and then dip the cooked pieces into sauces. While in Japan the origin has become a subject of debate, the cooking style is considered to be originally from Korea, derived from the Korean BBQ tradition of bulgogi, introduced to Japan by Korean immigrants in the 1920s

Sashimi

After sushi, the most popular sushi bar dish is a delicacy of fresh highest-quality raw fish or meat sliced into thin pieces, often eaten with only wasabi and soy sauce. Most common ingredients used in the preparation of sashimi are tuna, squid, scallop, whale, and octopus. Sashimi and sushi share a common history, as both dishes were originally prepared during the 8th century in Southeast Asia. Typical types of sashimi include: Maguro (tuna), Buri (yellowtail, or Japanese amberjack), Sake (salmon), Ikura (salmon roe), Uni (sea urchin). Shiro maguro (albacore tuna). The history of sashimi is opaque, though historically, the first sighting of sashimi or consumption of sliced raw fish was first recorded in China around 823 B.C. Afterwards the custom may have fallen from popularity due to lack of refrigeration and food poisoning or parasites. Sashimi gained popularity during the Edo period (1603-1868) evolving into a recognized dish, due to the great supply of fresh fish suitable for raw consumption in the Edo (Tokyo) area and the mass production of soy sauce which acts as a preservative with its high sodium levels and enhanced the flavor of the raw fish. Two other popular variations of the custom are poke in Hawaii and ceviche in in Latin America.

Soba

Soba is the Japanese name for buckwheat and synonymous with the type of thin bluish-hued noodle made from buckwheat flour, although in Japan soba can refer to any thin noodle (unlike thick wheat noodles, known as udon). Known as zaru soba, cold soba dish is eaten by dipping long noodles into a dipping sauce to which wasabi (Japanese horseradish) and green onions are often added.

Yakizakana

A traditional Japanese breakfast will often include a serving of yakizakana. Served straight from the grill, yakizakana (literally, grilled fish), with a bowl of rice and miso soup comprise the quintessential Japanese meal. Many varieties of fish are enjoyed in this way, including mackerel (saba), salmon (sake), mackerel pike (sanma), horse mackerel (aji), Okhotsk atka mackerel (hokke), sea bream (tai) and sweetfish (ayu).

Sukiyaki

Sukiyaki is typically prepared right at the table, hot-pot style just like shabu shabu, by cooking thinly sliced beef together with vegetables, tofu and vermicelli. In Japan, sukiyaki is typically a winter dish and it is commonly found at bōnenkai, year-end binge drinking parties with co-workers or friends.

Tempura

Tempura is everyone's favorite deep-fried dish. After being coated with a mixture of egg, water and wheat flour, fried in vegetabel oil. Among the ingredients used are shrimp (omigod), fish in season, and vegetables.

Honzen ryori

Honzen ryori is one of the three basic styles of traditional Japanese cooking yet regarded as Japan's most exquisite culinary refinement. Honzen ryori is a highly ritualized form of serving food in which prescribed types of food are carefully arranged and served on legged trays (honzen). Honzen ryori has its main roots in the socalled gishiki ryori (ceremonial cooking) of the nobility during the Heian period (794 - 1185). Although today it is seen only occasionally, chiefly at wedding and funeral banquets, its influence on modern Japanese cooking has been considerable.

The basic menu of honzen ryori consists of one soup and three types of side dishes - for example, sashimi (raw seafood), a broiled dish of fowl or fish (yakimono), and a simmered dish (nimono). This is the minimum fare. Other combinations are 2 soups and 5 or 7 side dishes, or 3 soups and 11 side dishes. The dishes are served simultaneously on a number of trays. The menu is designed carefully to ensure that foods of similar taste are not served. Strict rules of etiquette are followed concerning the eating of the food and drinking of the sake. For example, it is proper to eat a bit of rice before passing from one side dish to the next. An example of this formalized cuisine, which is served on legged trays called honzen.

Kaiseki ryori

Similar, but a less formal variation of Honzen ryori is the famous traditional multicourse Japanese-inn meal, kaiseki. Finer Japanese inns (ryokan) generally serve sumptuous multiple-course kaiseki-style meals such as the one shown. Vegetables and fish feature, with a seasoning base of seaweed and mushrooms. Although the basic features of kaiseki ryori can be traced to the more formal styles of Japanese cooking - Honzen ryori and chakaiseki ryori - in kaiseki ryori one may enjoy their meal in a relaxed mood, largely free of the elaborate rules of etiquette. Today this type of cooking can be found in its most complex form at first-class Japanese-style restaurants (ryotei). Sake is drunk during the meal, and, because the Japanese customarily do not eat rice while drinking sake, rice is served at the end. Appetizers (sakizuke or otoshi), sashimi (sliced raw fish; also called tsukuri), suimono (clear soup), yakimono (grilled foods), mushimono (steamed foods), nimono (simmered foods), and aemono (dressed salad-like foods) are served first, followed by miso soup, tsukemono (pickles), rice, Japanese sweets, and fruit. Tea concludes the meal. The types and order of foods served in kaiseki ryori are the basis for the contemporary full-course Japanese meal.

Kaiseki has international fans at the highest echelons of cooking, including Chef Kyle Connaughton of Single Thread in Sonoma, who notes his own attraction to the tradition is "The foundation of kaiseki is that the menu is not the same as yesterday or tomorrow, but focuses on that day, that moment in nature."

Shojin ryori

A is a type of vegetarian cooking introduced into Japan together with Buddhism in the 6th century. Shojin is a Buddhist term that refers to asceticism in pursuit of enlightenment, and ryori means “cooking.” In the 13th century, with the advent of the Zen sect of Buddhism, the custom of eating shojin ryori spread. Foods derived from soybeans - including tofu - and vegetable oils - including sesame, walnut, and rapeseed - were popularized in Japan as a result of their use in shojin ryori.

Yakitori

Instantly recoginized, and most everyone's favorite street snack are these savory grilled chicken skewers grilled to order over a white charcoal fire (binchō-tan) and seasoned with falt or tare sauce. Yakitori is made up of small pieces of chicken meat, liver and vegetables skewered on a bamboo stick and grilled over hot coals, essentially Japanese BBQ and similar to satay. Note that the term "yakitori" can also refer to skewered food in general. Yakitori are particularly popular among salarymen after work, and, together with ramen-ya, a popular place to go for a late night snack after drinking. Yakitori became popular in Japan after the war when Americans introduced chicken that are bred specifically for the purpose of meat consumption, thus lowering the cost for everyday Japanese.

There are primarily two types of ingredients that are used in yakitori, one using only plain salt and the other using tari sauce that is created from mirin, a type of rice wine, sake, soy sauce and sugar and provides it's sweet and salty taste. Chefs also season the yakitori with wasabi, a Japanese spice called shichimi, Japanese pepper, cayenne pepper or black pepper.

Tonkatsu

Tonkatsu is one of the most popular Western-style dishes in Japan featuring a pork chop is breaded with flour, egg, panko (bread crumbs), and then deep fried. There are two types of tonkatsu—hire (pork filet) and rosu (pork loin), served with shredded cabbage, a thick type of Worcestershire sauce (called tonkatsu sauce, or simply sōsu, meaning sauce), karashi (mustard), and a slice of lemon. Tonkatsu isusually served with rice, miso soup and tsukemono and may also be served with ponzu and grated daikon instead of tonkatsu sauce. An outstanding kid-friendly favorite.

Shabu-shabu (shäbo͞oˈshäbo͞o)

You will no doubt recognize the name of one of Japan's most popular exported dishes. Shabu-shabu (also spelled shyabu-shyabu) features tender, thin slices of beef held with chopsticks and swished around in a pot of boiling water, then dipped in sauce before being eaten along with vegetables. Other versions of Shabu-shabu use pork, crab, chicken, lamb, duck, or lobster. The dish is related to sukiyaki in style as both consist of thinly-sliced meat and vegetables and served with dipping sauces. However, shabu-shabu is considered to be more savory and less sweet than sukiyaki.

With shabu-shabu the meat and vegetables, which are cooked at your table grill, are usually dipped in ponzu or goma (sesame seed) sauce before eating, served along with a bowl of steamed rice. Once the meat and vegetables have been eaten, leftover long-simmering broth from the pot is customarily combined with the remaining rice, and the resulting fabulous tasting soup is eaten last. The dish origins are traced back to the Chinese hot pot known as shuan yang rou.

Sukiyaki

A nabe dish prepared with thinly sliced meat, vegetables, mushrooms, tofu and shirataki (konyaku noodles) simmered in a sweet soy sauce broth with pieces food dipped into raw beaten egg before being eaten. Sinilar to shabu shabu but sweeter in taste.

Soba and Udon

Soba and udon are the two most popular kinds of noodles in noodle-crazy Japan. Soba is made from buckwheat flour giving it a bluish color while udon is made from wheat flour. Both are served either in a broth or dipped in sauce and are available in hundreds of variations.

Specialty Japanese Restaurants & Food Places

Note that "ya" translates in Japanese roughly as "shop."

Sushi-ya

of course, sushi-ya are restaurants specialize in sushi. In most sushi-ya, customers can sit either at a normal table or at a counter (sushi bar) facing the sushi chefs as they are working which is the custom also in Western sushi places.

Kaiten-zushi

Kaiten-zushi, literally “rotation sushi”are less expensive sushi restaurants where sushi dishes conveneiently pass by customers on a conveyor belt. Diners freely pick the dishes that they like as they pass in front of them or may also order dishes which are not available on the belt. The sushi is priced per plate with differently colored plates corresponding to different price tiers (typically 100-800 yen per plate) or by a flat rate. In the end, the plates are counted and the total amount to be paid is determined. The style of dinign was invented by chain restaurant owner Yoshiaki Shiraishi and is credited with popularizing sushi around the world.

| Kappabashi AKA "Kitchen Town" For foodies and culinary professionals interested in more than food, Kappabashi street is a must visit. Several blocks long, the street Kappabashi-dori also called "kitchen town" is lined with stores, including commercial restaurant supply vendors seeking everything from bar stools to high-end knives, to the kitchen sink, but the most famous attraction there is the plastic imitation food in hundreds of varieties.

|

Soba-ya and Udon-ya

As the term implies, soba-ya specialize in soba and udon noodle dishes. Most noodle dishes are served in a hot broth or come cooled with a dipping sauce on the side. The noodles may be ordered with different toppings such as tempura or vegetables, and the menu often changes with the seasons.

Ramen-ya

Ramen-ya specialize in ramen—Chinese style noodles served in a soup along with various toppings. Every ramen-ya has usually developed its own soup, the most crucial ingredient for a restaurant's success. Several other dishes of Chinese origin, such as gyoza and fried rice, are also usually available at ramen-ya.

Karē-ya

Karē-ya specialize in Japanese style curry rice that is one of the most popular dishes in the country. Karē ("KAR-RAY") is commonly served in three main styles: over rice, udon, and bread. Cheap and quick, there are usally kare-ya and ramen-ya inside or around major railway stations for commuters.

Gyudon-ya

Gyudon-ya specialize in beef domburi—sake and soya sauce simmered beef and onion served over a bowl of steamed rice.Gyudon-ya are among the most inexpensive fast food style restaurants and are found all across the country.

Okonomiyaki-ya

Okonomiyaki-ya specialize in okonomiyaki (see paragraph above), savory pancakes, and sometimes monjayaki (pan-fried batter with various ingredients). In some places, customers prepare their okonomiyaki by themselves on a hot plate built into the table.

Yakitori-ya

Most everyone's favorite street snack is common in street stalls and carts using portable grills and causal eateries. Yakitori-ya are small shops that specialise in take-out only yakitori.

Tonkatsu-ya

Oh my, sinful and hard to resist for many diners. Tonkatsu-ya serve tonkatsu, deep fried breaded pork cutlets. A surprisingly recent and Western-inspired creation, tonkatsu can be used with other ingredients as part of an entirely different dish, such as curry. Korokke and other deep fried dishes are also available at many tonkatsu-ya.

Tempura-ya

As its name suggests, these restaurants specialize in tempura, such as tendon (tempura domburi) and other assorted tempura. A theory of the dish is that battered and deep-fried food was introduced into Japan by the Chinese, and then initially embraced by Zen monks who wanted to make their vegetarian diet more tasteful. The best ingredients for tempura are shrimp, scallops, squid, and small crabs, or vegetables such as shiitake mushrooms, asparagus, Japanese eggplant, and snow peas.

Unagi-ya

Unagi-ya specialize in unagi (fresh water eel) dishes such as unajuu, unagi nigiri sushi, grilled eel served in a box over rice, and unadon (unagi domburi).

Sukiyaki-ya & Shabu Shabu-ya

Sukiyaki-ya specialize in sukiyaki and shabu-shabu hot pot. Sukiyaki is a communal style dish, served in one pot, then shared among a larger group of people. They are often found in large, Western style hotels.

Teppanyaki-ya

At teppanyaki restaurants, the chef is preparing meat, seafood and vegetables on a large iron griddle (teppan) in the presence of the customers who sit around the griddle. Teppanyaki restaurants are commonly found at hotels and are usually pretty expensive. They are a popular place to enjoy premium Japanese beef (wagyu) such as kobe beef.

Japanese Restaurant Types

Dining places can vary from pubs to food carts, typically offering a broader range of dishes than specialized ones above.

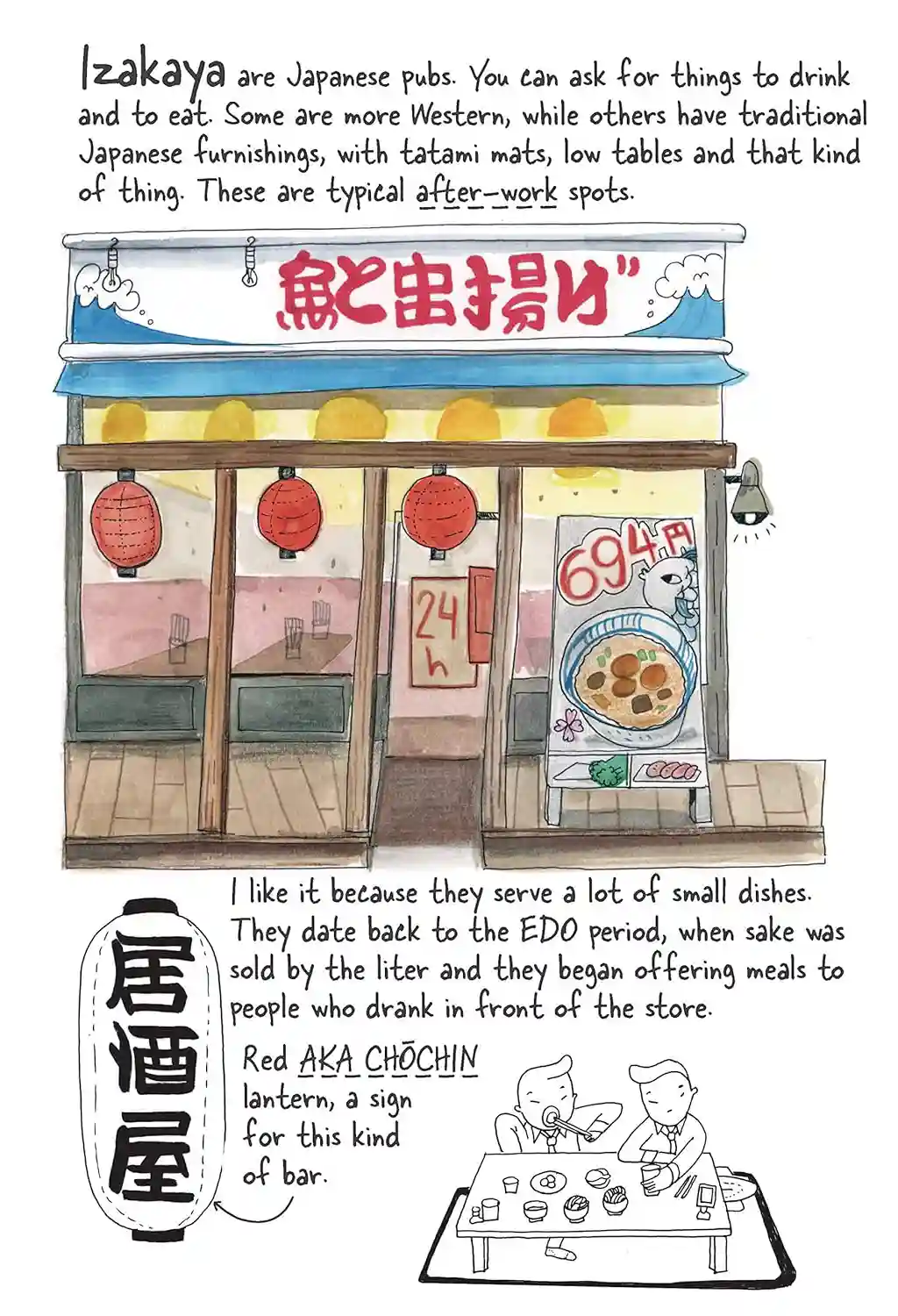

Izakaya

Izakaya (居酒屋) - "stay saké shop"), like pubs, are casual drinking establishments that also serve a variety of small dishes, such as robata (grilled food), yakitori, salads and other finger foods. They are the most popular restaurant type among the Japanese, and many of them are found around train stations and shopping areas. Dining at izakaya tends to be informal, with dishes shared amongst the table rather than eaten individually. [Sketch below from: Tokyo Travel Sketchbook by Amaia Arrozola].

Family Restaurant (Famiresu)

Family restaurants, represented by such chains as Gusto, Royal Host, Saizeria and Joyful, are casual dining restaurants that typically belong to a nationwide chain and offer a variety of Western, Chinese and Japanese dishes. Family restaurants are more commonly found in the countryside than in large urban centers.

Shokudo

Shokudo are casual restaurants, similar to family restaurants, but tend to be small, independently owned and feature mostly Japanese style food such as soba, udon, donburi and curry. Shokudo are commonly found around tourist sites.

Teishoku-ya

Teishoku-ya "diners" serve budget-friendly set menus (teishoku). Teishoku typically consists of a main dish such meat of fish, a bowl of cooked rice, pickles and miso soup. Teishoku-ya are causal places especially numerous in business areas and busiest during lunch time.

Kissaten (Coffee Shops)

Kissaten "tea-drinking shop" are actually old-style coffee shops that typically also serve some sweets, sandwiches or salads. Some of them also offer a few hot dishes, such as pasta. They are often found in museums, shopping areas and department stores. Known mostly from another era like diners in the U.S., they are often run by older generations, they are disappearing in favor of cafes (kafe), which are hipper and also serve alcohol.

Kaiseki Ryori & Ryotei

A cultural ritual and a meal. Kaiseki or kaiseki-ryōri is Japan's haute cuisine, a refined traditional multi-course cooking style which emphasizes seasonality, simplicity, aesthetics, and elegance to the point of ritual. It can be found at special kaiseki ryori restaurants or at ryotei, expensive and exclusive Japanese restaurants while many finer ryokan also serve kaiseki ryori. Its origins are found many centuries ago in the simple meals served at the tea ceremony, but later kaiseki evolved into an elaborate dining style popular among aristocratic circles with similar ritual of the tea ceremony. Kaiseki is a highlight of staying in a ryokan.

Kaiseki-style meals are usually served in a set order, kaiseki chefs emply great leeway in courses served to highlight regional and seasonal specialties and their own personal style. The order of kaiseki usually includes appetizers with alcohol, soup, sashimi, nimono (boiled ingredients), tempura, chawanmushi (custard), sunomono (vinegared dish), and at the end of the meal, shokuji, a set of dishes of of rice, miso soup and pickles (tsukemono) followed by dessert. Be aware, having kaiseki meals can be a challenge and we recommend spacing your meals.

Yatai (Food Carts)

Nestled within the bustling streets and serene parks of Japan, the Yatai food carts emerge like culinary beacons as the sun sets, igniting the night with a warm glow and the irresistible aromas of street-side cooking. These mobile food stalls are a testament to the enduring charm of traditional Japanese street food culture, offering a tantalizing window into the soul of Japan's rich gastronomy. Yatai are much more than mere sources of sustenance; they are vibrant hubs of human connection, encapsulating the essence of Japanese omotenashi—unparalleled hospitality. With their noren curtains fluttering in the evening breeze, these quaint carts invite passersby to take a moment from their hurried lives and savor not only food but also camaraderie.

Watch a Yatai vendor in Fukoka

Each Yatai, often manned by a single chef, is a treasure trove of flavor, with menus that often specialize in a select few dishes perfected over time. From sizzling yakitori skewers to steaming bowls of ramen, from the delicate balance of a fresh okonomiyaki to the comforting simplicity of takoyaki balls, each dish is crafted with meticulous care. The history of Yatai is deeply interwoven with the seasons and festivals of Japan, with their presence peaking during matsuri where they serve as culinary companions to the festivities. But even on a regular day, these carts stand as cultural sentinels, offering a bite of tradition in the rapidly modernizing landscape of Japan. So pull up a stool at the counter of a Yatai and watch as the chef works his magic, flipping, frying, and garnishing with the expertise of years! As you take your first bite, listen to the chatter that fill the air, and immerse yourself in the living tapestry of Japanese street food culture that the Yatai so proudly represent.

Popular Street Food Districts in Japan

Golden Gai & Shinjuku Omoide Yokocho (Shinjuku, Tokyo)

An vintage area of Tokyo with hundreds of bars and the nearby narrow warren of alleys near Shinjuku Station are busy with small eateries and street food stalls. Indulge in grilled meats, yakitori, yakisoba, and and local favorites including buta no kakuni (braised pork belly) and motsu-nikomi (offal stew).

Nakamise Street (Asakusa, Tokyo)

Nakamise Shopping Street leads up to the iconic Senso-ji Temple and is a busy pedestrian area famed for its many traditional food stalls. Enjoy a variety of treats such as ningyo-yaki (doll-shaped cakes), freshly made senbei (rice crackers), melon pan (sweet bread), and matcha-flavored snacks. The street also is also a terrific spot to browse for souvenirs.

Takeshita Street (Harajuku)

Situated in the trendy Harajuku district, Takeshita Street has long been renowned for quirky fashion and bold street food scene. Here, you can explore a diverse array of treats, from crepes and cotton candy to rainbow-colored snacks and savory delights like takoyaki (octopus balls) or yakisoba (fried noodles), many of these prepared on the spot.

Pontocho (Kamo River, Kyoto)

Pontocho (先斗町, Pontochō) is one of Kyoto's most atmospheric dining districts. This narrow alley stretches from Shijo-dori to Sanjo-dori, one block west of the Kamogawa River. Lined with restaurants on both sides, Pontocho offers a wide array of dining options, ranging from affordable yakitori to traditional and modern Kyoto cuisine, as well as international dishes. Some highly exclusive establishments also require the right connections and a generous budget. Many of the restaurants on the eastern side of the alley provide scenic views of the Kamogawa River.

Dōtonbori (Minami, Osaka)

The vibrant entertainment district of Dotonbori is Osaka’s most famous tourist destination, celebrated for its dazzling neon lights, bustling crowds, and an extensive array of restaurants and bars. It is also renowned for offering some of the best street food in all of Japan.

Sanmachi (Takayama)

Sanmachi, the main area of Takayama encompasses six neighborhoods of "Little Kyoto" and features Edo-period traditional buildings of shops, restaurants, with busier streets offering all kinds of street food that you may enjoy while strolling around town. Standout snacks include Hida beef sushi, beef skewers, beef buns, rice dumplings, gohei mochi (grilled glazed rice cakes), and a unique variety of savory sweets.

Culinary Activities in Japan

Tokyo Food Tour

Explore the culinary delights of Tokyo with our crafted dining tours. Enjoy savory fresh sushi at the wholesale market, Tsukiji, followed by snacking world-famous street eats in Asakusa. In Shinjuku, enjoy a range of casual delicious fare served up at bustling izakaya (informal pubs), and other dishes through the day, including sashimi, kushiage, robata grill, kushiyaki (grilled meat or vegetable skewers) kamen, and savory okonomiyaki ( a type of Japanese pancake), kaiten-zushi (conveyor belt sushi), and more formal dining, including world-renowned sushi at Kyubey and Sushi Saito.

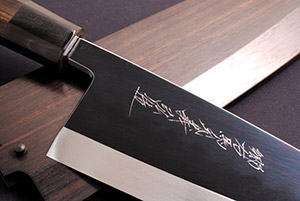

Tokyo Sushi Cooking Class

What could provide more cultural immersion than a sushi cooking class in Tokyo? This full-day culinary experience offers exposure to more than sushi, including a visit to the Toyosu fish market with a top chef to areas of the market off limit to tourists, as well as stroll through a popular street food and a local foods market. During your private class with an experienced chef, not only master making nigiri sushi, but also learn about traditional ingredients and how they are grown and made, as well as the cooking tools and techniques used to prepare other Japanese cuisine employing specific utensils and fresh, seasonal, traditional local ingredients and recipes. The class concludes with dining on your delicious and hard-earned creations accompanied by sake in celebration.

Kyoto Kaiseki Cooking Class

Enjoy a half, full-day. or week-long cooking class mastering the various dishes of traditional kaiseki. Kaiseki is considered Japan's highest form of culinary style, characterized by extreme sophistication of the taste and the appearance, carefully selected seasonal ingredients, and the chef's meticulous attention to the arrangement of the vessels and space, and ritualized serving of dishes. Learn about kaiseki's association with the concept of wabi-sabi (art of imperfection and impermanence) and the five elements of yin-yang. Class also features vistis to local farms and Nishiki Market, the oldest wholesale foods market in Japan.

Osaka Street Food Crawl

Osaka is known as "Japan's Kitchen," a city obsessed with and that excels in cuisine. Explore the legendary food market, Kuromon Ichiba, vintage Osakan alleys Shinsekai and Nishinari. that still retain many of the old eating and drinking places serving many menu items unique to the area. Learn about Japanese comfort food such as oden, a one-pot dish with a varying assortment of stewed ingredients simmering in the same pot, famous takoyaki (octopus balls), oshizushi, or “pressed sushi”, a type of sushi distinct to the Kansai region that’s molded in a box, and kushikatsu, fried skewers of meat, fish, and vegetables. Note that vegetarian and pescatarian food tour and options are available, however dairy free and vegan options are unfortunately not.

Vegetarian Dining in Japan

One of the world's most varied and complex cuisines is surprisingly a challenge for vegetarians. Vegetarians will find Japan a typical Asian country where although meat is typically served in limited quantities, it is somewhat difficult to fully escape flavorings, sauces, and seasonings may use fish products or other meats. For example, seemingly vegetarian tempura may be made with egg batter and dashi, a fish-based cooking stock, is widely used in what appear to be vegetarian dishes.

What to say? "Watashi wa bejitarian desu" – I am vegetarian.

Tokyo Vegetarian Restaurants

- Kureyonhausu (Omote Sando): https://tabelog.com/tokyo/A1306/A130602/13055370/

- Pure Café (Omote Sando): http://pure-cafe.com/

- La Longe Vita: https://lalongevite.jimdo.com/

- Fancl (Ginza): http://www.fancl.jp/ginza-square/food/dorobushi-kitchen.html

- Tamana Shokudo (Minato-Ku): http://nfs.tamana-shokudo.jp/?page_id=1589

- Nataraj (Indian, chain – citywide): http://nataraj2.sakura.ne.jp/cafe3/language.html