Vietnamese Cuisine

Richard Sterling wrote that "if cooking were painting, Vietnam would have the world's most colorful palettes." People tend to know two things about Vietnam: that it endured a long and painful war, and that it has one of the richest, most varied cuisines in the world. Everything you've heard is true—Vietnam is the ultimate "food adventurer" destination. Famous dishes such as pho and spring rolls are but the tip of a gastronomic iceberg, with an immense number of local styles and regional dishes, limited only by the imagination of local cooks. It is a place where the best things to eat are not only found in the atmospheric courtyards of elegant French villas, but also at the ends of tiny alleys where diners are packed in curbside atop small plastic chairs, or tucked away on the upper floors of rustic concrete buildings.

Vietnam Culinary Trips

We began organizing our Iron Chef Vietnam culinary journeys over twenty years ago. Why Vietnam? Of all the destinations to enjoy a culinary-focused tours, it is in Vietnam where food really shows the heart and soul of a nation. You can sense it in every meal, whether a breakfast overlooking the rice paddies or a dinner in an opulent city restaurant. Food is a topic of conversation with the locals you meet, an ice-breaker for conversing with strangers. It's an invite to explore, with markets and alleyways so vibrant in their fragrances and flavors.

Mastering spring rolls in Hoi An

Mastering spring rolls in Hoi An

We can blend in a mix of culinary highlights, from informal street eats to formal dining, including specific culinary activities experiences in your trip, such casual to serious-level cooking classes and markets. But more than that, ensure that the country's gastronomic pleasures become part of your every day, instilling the heart and soul of a country into every bite.

![]() Read more about our foodie and culinary trips in Vietnam

Read more about our foodie and culinary trips in Vietnam

A (short) introduction to Vietnamese cuisine

"The Vietnamese are a skinny people obsessed with food" claimed Anthony Bourdain.

Vietnamese cuisine is vast and varied, always subject to innovation, and always vibrantly colorful. In their food, you'll encounter the wonderful and the strange, the sacred and the profane. You'll find spices that sing in your mouth, smells that trigger emotions, dishes that amaze by their cleverness and beguile by their sensuousness, drinks that surprise, fruits that will shock and creatures that will make you shriek. Above all, you'll find the people that make up Vietnam's food culture who will charm, frustrate and intrigue you. You will consume a culture more than anything else. A culture that is still relatively poor in goods but rich in history, art, literature, music and pride. A culture that will reveal itself to you, if you are willing and hungry enough, through the medium of its cuisine. Vietnam lays itself bare in the kitchen and at the table. Its history, its legends and its lore are all reflected in its food and drink.

Historians like to say that geography is fate. Geography is also cuisine, for it determines what foods and what people may shape it. The topography of Vietnam presents virtually every climate and micro-climate capable of yielding a crop or animal, whether tropical or temperate, from fish, rice and tea to beef, coffee and cream. A Look at the map of Vietnam. As the Vietnamese are eager to point out, it resembles a don ganh (a yoke), a bamboo pole with a basket of rice slung from each end. The baskets represent the main rice-growing regions of the Red River Delta in the north, and the Mekong Delta in the south. Notice too on this symbolic map of Vietnam its waters with 1,500 miles of coastline and its innumerable rivers and streams.

Rice cultivation and the harvesting of the water world provide the cuisine of Vietnam with its two most potent symbols and substances: rice and nuoc mam (fermented fish sauce). This pair makes up the sine qua non of Vietnamese food. With them, Vietnamese cooks can go anywhere and still prepare something at least close to their native fare.

In keeping with its geography, Vietnamese cooking is heavily influenced by China, especially in methods of preparation and cooking tools. They share the concept of "the five flavors"— a balance of salty, sweet, sour, bitter and hot (spicy). A dish may be dominated by one or two of the five, but the others will usually play a pleasing harmony in the culinary chorus. Stir frying is typical for cooking, but Vietnamese generally use very little oil, with a lighter hand than the Chinese. The frying is more of a gentle simmering in the expressed juices of the food, producing lighter and fresher dishes—the most marked difference from Chinese food.

As in China, vegetables play a central role in cuisine, but in Vietnam they are raw as often as cooked and fresh herbs are applied abundantly. Vietnam's fish and seafood are plentiful, and of great variety. Fish are generally alive at the time of sale, and deftly killed and cleaned by the merchant upon selection (Vietnamese cooks rightly point out that fish are more flavorful if they are not deboned before cooking).

Like Chinese food, varying textures such as crunch and chewiness are prized at the Vietnamese table. Seasoning all dishes is nuoc mam (they seldom use soy); like a judicious splash of Worcestershire sauce, when cooked into a dish it buries itself in the flavors of the food and gives it greater dimension without altering its basic character. Also important are the fire spices, chili and black pepper. Normally they are not cooked into the food but served as condiments, and are used as commonly as salt. Sweet spices such as star anise and cinnamon, and pungent ginger are common. Vinegar is not widely used with acidity provided by tamarind and lime.

The Vietnamese have three styles or manners of cooking and eating: comprehensive eating, or eating through the five senses; scientific eating, which observes the dualistic principles of yin & yang; and democratic eating, or the freedom to eat as you like. In comprehensive eating, the most common form, you eat with your eyes first. Dishes must be attractively presented with a diversity of forms and colors. Then the nose follows: the Vietnamese penchant for aroma is brought to the fore, and each dish must offer pleasant odors of meat, Fish or vegetables and a sauce. When chewing, take care to feel the softness of noodles, the texture of the meat, and listen to the crackling sound of rice crackers or the crunchiness of roasted peanuts. And then you taste. The cook must see to it that each dish prepared has its own distinct flavor, and you, the diner, should take note of the differences. Although a dish might have all the five flavors, but should dominate.

Scientific eating concentrates on the dualistic philosophy of yin & yang, in this case a balance between hot and cold. For instance, a fish stew would be seasoned with salty fish sauce which is yang, but balanced by the yin of sugar. Green mangoes (yin) should be taken with salt and hot chilies (yang); grilled catfish or duck (yin) must be eaten with ginger ;yang). This kind of eating is said to contribute to the good health of both mind and body.

By Richard Sterling ("the Indiana Jones of Gastronomy"), from his World Food Guide Vietnam (see Richard's other blog and books, including a favorite, Dining with Headhunters, a collection of curry recipes along with tall travel tales).

Vietnamese—the Healthiest of Cuisines

Vietnamese food is the original farm-to-table cuisine, always marked by freshness. It is also one of the world's healthiest, reflected by the longevity and robust health of the Vietnamese. This is not the greasy, MSG-laden, deep-fried Asian dishes of mall buffets, but the lightest and freshest of all Asian cuisines featuring small portions of lean meat in dishes, gluten-free by default, lots of fresh vegetables, and cooked in water and broth rather than oils. Herbs, not heavy sauces add flavors. Everyday, street vendors prepare dishes with fresh vegetables, herbs, and meats from scratch, featuring local in-season produce. Xalach dia, for example, is a table salad of assorted fresh herbs, salad greens, and sprouts, and vinegared vegetables that comes as an accompaniment to almost every meal, and there are always fresh condiments on hand. One of the most pleasurable aspects of eating Vietnamese food is the act of sampling, altering, and enhancing your food as you eat. Vietnamese soups also exemplify the freshness, with complex flavors, and the flexible do-it-yourself aspect of Vietnamese cuisine, with fresh leaves, sprouts, sauces, and herbs served alongside to add by preference. Vegetarians will be pleased by the variety of meat-free dishes in this Buddhist culture, where vegetarianism is widely practiced and tofu is popular with everyone.

Vietnam—Vegetarian paradise

Vietnam—Vegetarian paradise

Large bowls of pho (hot soup) are a favorite breakfast in Vietnam, and can also be found in stalls and restaurants later in the day. The soups are famously hearty and delicious. The Vietnamese are also known for their soup broths filled with noodles, bean sprouts, sprigs of fresh herbs, and lean pieces of chicken, pork, or beef. Garnish your soup with more fresh herbs or sprouts from the table salad, or with any of the many little sauces and condiments that may be set out.

Vietnamese dipping and flavoring sauces are varied, tasty, and addictive. The most common of these is known as nuoc mam, pale blend of salty, pungent fermented fish sauce diluted with fresh lime juice and sometimes vinegar, spiced with garlic and chopped chilies, and sweetened with a touch of sugar. You can drizzle it over your rice, use it as a dip for spring rolls or grilled meats, or add a spoonful to your soup. It is delightful with French fries (and the Vietnamese make some of the best fried you will ever have). Other dipping sauces include nuoc leo, a peanut sauce from the Hue region now widely found throughout the country; tuong ot, a red hot chili sauce similar to the famed sriracha, and mam tom, a pungent shrimp sauce also from central Vietnam. One of our favorite condiments is a simple combination often served at soup stalls and restaurants: a pile of black pepper and a pile of salt placed side-by-side on a small dish and served with a wedge of lime. You squeeze a little lime juice into the dish and blend some salt and pepper with it to make a paste into which you dip bits of grilled meat or meat from your soup.

Roll Your Own

The other do-it-yourself element in many Vietnamese meals comes with roll-your-own rice-paper rolls. For example, grilled chunks of lemon grass beef (thit bo nuong), grilled meatballs (nem nuong), or freshly steamed shrimp (tom) all come served with a salad plate together with a stack of moist rice papers (banh trang) or fresh rice wrappers (banh uot). You lay a wrapper on your open palm, place your ingredients into the moist, pliable rice paper to roll. If you're traveling to Halong Bay with us, you'll have a chance to prefect the spring roll with your on-board chef (right).

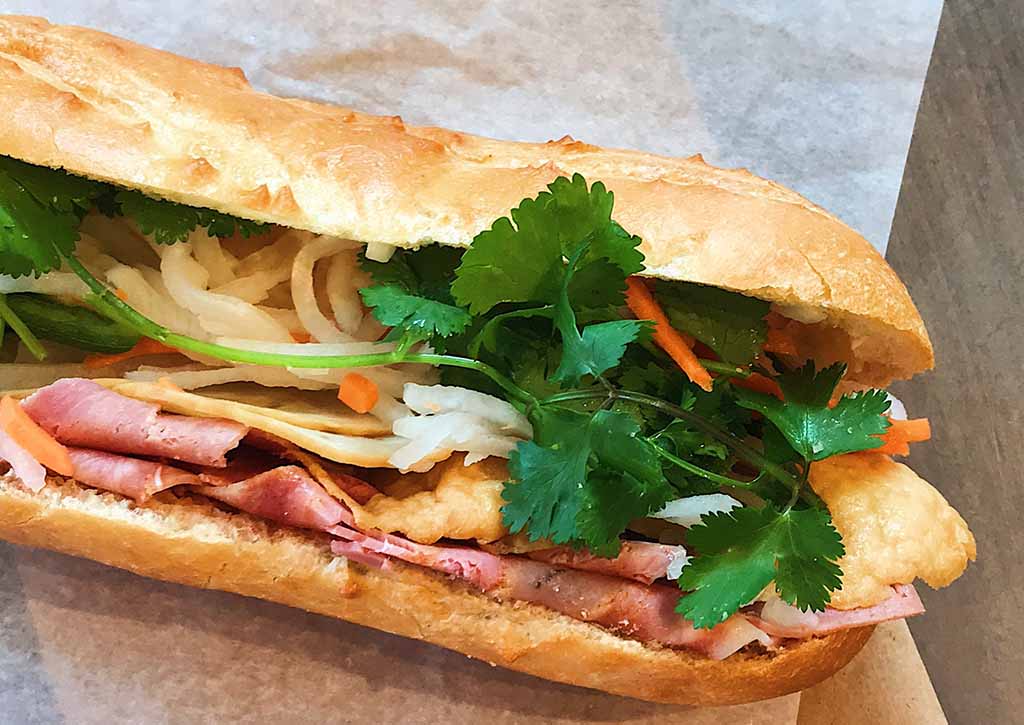

The Vietnamese Deli

Banh mi (sandwiches) are a perfect example of the Vietnamese adoption of foreign culinary offerings and expounding on them, In this case, French baguettes. Made to order from these delicious fresh French-style baguettes (the Vietnamese baguette version is lighter with a thinner the crust) are quick to go sandwiches. It usually includes pickled strips of white radish and carrot, then you can choose a selection of pates and cured meats and other additions, or simply ask for the works—bánh mì đac biet—(though you may want to avoid mayonnaise as a health precaution).

Banh mi (sandwiches) are a perfect example of the Vietnamese adoption of foreign culinary offerings and expounding on them, In this case, French baguettes. Made to order from these delicious fresh French-style baguettes (the Vietnamese baguette version is lighter with a thinner the crust) are quick to go sandwiches. It usually includes pickled strips of white radish and carrot, then you can choose a selection of pates and cured meats and other additions, or simply ask for the works—bánh mì đac biet—(though you may want to avoid mayonnaise as a health precaution).

Baguettes made from rice flour are sold in street stalls from Haiphong to the Mekong Delta from midmorning until after sunset; when there's a choice, go for the vendor who heats the bread on a grill before assembling the sandwich. You'll see a small charcoal brazier by the side of the stall or under the sandwich cart. Don't buy your sandwich late, by the afternoon the bread is now really only useful as a hard-edged weapon. To go with your bread, pate or cheese? The pate is homemade, the consistency of Spam, and wrapped in banana-leaf. Spam pate is usually made from pork. Cheese is usually processed in boxed segments; try either the Laughing Cow variety (La Vache Qui Rit or Vache Jolie) or the sterner non-laughing cow (Nouvelle Vache). Palatable, but poor quality. There's a cake shop in Hanoi that makes cheese similar in taste to feta. Another topping is jam, another French transplant. Varieties include papaya and pineapple.

Ingredients of Vietnam Cuisine

The region and season greatly influences dishes and even ingredients for the same dish. The north tends to keep it simple, claiming the keeper role of traditional Vietnamese cuisine, while heading south, things tend to get a lot more looser and innovative, in part to wealth. For example, the national dish—pho—is made plain and unadorned in beef broth simmered for hours, but when arrives into Ho Chi Minh City (Saigon), suddenly the size of the bowl doubles while ingredients, especially the herbs added—are exponential. Of course, each claims theirs style is best, but we'll leave that for you to decide.

Best pho in Vietnam? It's complicated....

Best pho in Vietnam? It's complicated....

Vietnamese food is mainly of fresh seafood, rice, and vegetables. Situated on the ocean and rivers (including the mighty Mekong), but without much land for grazing, fish and seafood are the main meat consumed in the country. Fresh catch of squid, shrimp, lobster, and many other marine varieties are plentiful. A pungent fish sauce, nuoc mam, is added to almost every dish and eaten at every meal, a foundation that most travelers come to enjoy. The lack of land for grazing, means chicken and pork appear in Vietnamese cuisine more often than beef, though the latter is the customary staple of pho, the national dish, in thin strips. Poultry follows seafood in availability, and small amounts of pork appear in many dishes.

As with other Asian countries, only small amounts of meat are typically added with larger amounts of vegetables and rice, and into soups. The Chinese coveted Vietnam for the massive and fertile rice growing areas in the Mekong and Red River deltas and the influence on the cuisine of Vietnam from their one thousand year occupation is expressed, mostly in the northern region, by tofu (bean curd), star anise, spring rolls, and Chinese-style soups. Similar to the Chinese also, Vietnamese make stir-fry dishes, and eat rice separately from the other dishes, rather than mixing them together like people from the south do. Rice accompanies all Vietnamese dishes, like in the other Southeast Asian cuisines, though Vietnamese prefer fluffy, separate grains of rice rather than the sticky rice favored in Japan and Korea, and neighboring Laos. Rice and noodles dominate the Vietnamese diet, although French-style bread adopted during the French occupation remains quite popular in banh mi.

French influence on the cuisine is also well represented, predominantly with the use of garlic, sauces, and butter. Generally, Vietnamese recipes contain a wide variety and ample amounts of fresh herbs; however, the use of spices varies from region to region, with far more usage in the south as there are fewer spices available in the north. Overall, the dishes tend to be less spicy in the north than those eaten in the south. Influence from the Indian cuisine appears in southern Vietnam in curries and various rice pancakes.

Unlike Chinese and other cuisines in Asia, little oil is used in cooking with simmering in broth and water applied more often than stir-frying—delicious spring rolls and French fries being two popular exceptions. Whereas Thai cuisine tends to be spicy or sweet, Vietnamese cuisines seeks a balance—not too much of any flavor, ingredient, or anything, for that matter. Northern food is often presented in a simpler, more natural, or "traditional" state. Soup is everywhere, another staple of Vietnamese cuisine, and is consumed almost daily from the start of the day, with breakfast coming in the form of a steaming bowl of fresh pho, a North Vietnamese rice noodle soup in a simmered beef broth strongly flavored with cilantro, garlic, and nuoc mam (fish sauce). Paper-thin slices of raw beef and rice noodles are placed in a bowl, and then covered with boiling broth, cooking the meat. Pho is traditionally garnished with paper-thin onions, fresh herbs, lime, chilies, and bean sprouts and far more herbs by the time the dish is prepared in the south. Like most Asian countries, all dishes are served at once. A Vietnamese "salad," takes the form of any variety of vegetables (and perhaps meat or seafood) which are wrapped in a lettuce leaf, then enclosed in a rice paper wrapper, dipped in nuoc mam sauce, and eaten. The Vietnamese table setting includes a saucer at each place setting for holding salt, pepper, nuoc man, and chili paste for dipping or adding to dishes.

Vietnam's Exotic Fruit Menagerie

By exotic, we mean fruit you have never seen let alone eaten. If you've not been to the region before, fruit will be a definite highlight of your Vietnamese culinary exploration. The country

offers a profusion of tropical fruit, especially in the Mekong Delta. These exotic specimens will  tickle your taste buds, quench your thirst, or at the very least arouse your curiosity. Among the rarer and more exotic are dragon fruit (thanh long)—shown right, found in the Nha Trang area, and water coconut (dua nuoc) and a three-segment coconut (that lot) from the Mekong Delta. Juice bars in the south turn out concoctions with crushed ice and sweetened condensed milk and other murky mixtures, called che bap. Fruit is also used to make a variety of jams and jellies. You can also get exotic items like custard apple ice cream in Saigon. Fruit is seasonal, and offerings vary from north to south. Durian (sau rieng) is a round, greenish fruit studded with sharp spikes. It's the size of a football, can weigh up to twenty pounds, though is available in the summer in the south. Broken open with a sharp knife, it reveals white pod like sections that have the texture of a very ripe French Camembert, which is why the fruit is nicknamed "the cheese that grows on trees." Despite its awful smell, durian has an exotic taste, described by 19th-century naturalist Alfred Russet Wallace thus: "A rich butter-like custard highly flavored with almonds gives the best general idea of it, but intermingled with it come wafts of flavor that call to mind cream cheese, onion sauce, brown sherry, and other incongruities." In Asia, the smooth and highly nutritious flesh of the durian is reputed to be an aphrodisiac.

tickle your taste buds, quench your thirst, or at the very least arouse your curiosity. Among the rarer and more exotic are dragon fruit (thanh long)—shown right, found in the Nha Trang area, and water coconut (dua nuoc) and a three-segment coconut (that lot) from the Mekong Delta. Juice bars in the south turn out concoctions with crushed ice and sweetened condensed milk and other murky mixtures, called che bap. Fruit is also used to make a variety of jams and jellies. You can also get exotic items like custard apple ice cream in Saigon. Fruit is seasonal, and offerings vary from north to south. Durian (sau rieng) is a round, greenish fruit studded with sharp spikes. It's the size of a football, can weigh up to twenty pounds, though is available in the summer in the south. Broken open with a sharp knife, it reveals white pod like sections that have the texture of a very ripe French Camembert, which is why the fruit is nicknamed "the cheese that grows on trees." Despite its awful smell, durian has an exotic taste, described by 19th-century naturalist Alfred Russet Wallace thus: "A rich butter-like custard highly flavored with almonds gives the best general idea of it, but intermingled with it come wafts of flavor that call to mind cream cheese, onion sauce, brown sherry, and other incongruities." In Asia, the smooth and highly nutritious flesh of the durian is reputed to be an aphrodisiac.

Also in the football-size league is the jack fruit (mit), a cousin of the durian. Jack fruit is bright yellow and very sweet and crisp with a sweet fragrance. The large hard seeds can be steamed, shelled, and eaten. Jack fruit can grow to monstrous proportions, with some specimens weighing in at 40 kilograms. As the fruit ripens, the skin turns from green to brown, and is covered with blunt spines. The tender fruit is either eaten raw or cooked in various sweet and savory dishes.

Rambutan (chom chom) has hairy reddish spines surrounding a translucent fruit that tastes like lychee. Similar tasting, but with a smooth exterior skin, is the smaller longan (trai nhan). Mangosteen (mang cut) has a leathery maroon husk with soft, delicious white flesh inside. The taste reminds Westerners alternately of cream, lemonade, and fragrant apple. When eating this fruit, avoid the large seed in the center, which can be bitter if bitten. Also watch out for mangosteen juice, which stains. Some fruit is used in salads or for other purposes. A fresh young coconut is often cut in half and the flesh scooped out with a spoon-ice cream and candied fruit can then be served in the shell along with the coconut I flesh. Star fruit (trai khe) is used in salads and juices; you'll know the cool, watery fruit inside is ripe when the waxy skin turns from green to deep yellow. Star fruit is also known as the star apple, or carambola.

A bit more familiar in taste for Westerners is the pomelo (buoi), a relative of the grapefruit and tasting similar, though it has a huge, husky exterior. Watch out for the translucent segment skin, which can be very bitter. Uglifruit (cam sank) is a grapefruit-tangerine hybrid, with dark green or mottled skin. It is often used for orange juice that is guzzled in Saigon. The persimmon (bong) looks like a tomato but has a stretched bright orange glossy skin. Inside, the fruit offers a smooth firm flesh.

A bit more familiar in taste for Westerners is the pomelo (buoi), a relative of the grapefruit and tasting similar, though it has a huge, husky exterior. Watch out for the translucent segment skin, which can be very bitter. Uglifruit (cam sank) is a grapefruit-tangerine hybrid, with dark green or mottled skin. It is often used for orange juice that is guzzled in Saigon. The persimmon (bong) looks like a tomato but has a stretched bright orange glossy skin. Inside, the fruit offers a smooth firm flesh.

The Java apple (man), also known as rose apple, is bright red, pale pink, or greenish, and has a sweet-and-sour acquired taste. The tiny Vietnamese apple is extremely sour and a bite will bring tears to your eyes, though it doesn't have much effect on the locals who happily munch away. Locals in the south also feed on tamarind, a bean-like fruit with a brittle skin, and pods that will make you pucker like you've never puckered before. The flesh is used to flavor curries, and also used for cleaning brass.

Quite unlike any apple you've seen before- or are likely to see again-is the custard apple (mang cau), a round fruit with a scaly, bumpy, green exterior. It looks like something from the Twilight Zone. Inside lies a white heart with black button-like seeds. Custard apple is excellent in fruit juices with a dash of orange juice. Pureed custard apple, watered down and pepped up with a little lime or orange juice, makes an exotic milkshake. In the same fruit family, with a similar taste but an entirely different appearance, is the spiny soursop (mang cau xiem), a longish fruit with a thin skin that has rows of dark green curved spines. The white pulp offers a delicious sour sweet flavor.

Most exotic of all is dragonfruit (thanh long), so named because it grows on a creeping cactus like plant said to resemble a green dragon. The fruit is oval-shaped, about the size of a small pineapple, magenta in color, with a smooth skin sprouting green petals. Inside, the pulpy and translucent white flesh is scattered with thousands of black crunchy seeds. The succulent flesh is an excellent thirst-quencher. The fruit is grown mostly in arid parts of Binh Dinh province around Qui Nhon, and is in great demand, with exports to Hong Kong, Taiwan, and China. Dragonfruit is in season May-September.

My Favorite Vietnamese Dish

I've lead trips for over 20 years and always enjoy taking visitors to my favorite places. The best eating in my country is on or close to the street. Many are surprised to taste the best soup they have ever had on the sidewalk! No matter who they are, even a Hollywood star or a Silicon Valley CEO, or an everyday traveler, all people enjoy discovering eating the local way in Vietnam.

Join me in Vietnam visiting my favorite places for a food adventure you will never forget.

—Canh Nguyen

Depth Charge Coffee, Traditional Tea, and other Libations

Fresh coconut milk is not only a delight but refreshing in Vietnam's warm tropical climate. Vendors deftly cut the top off a young coconut and serve with a straw. After you drinking the vendor will hack it open for you to scoop out the flesh. Street sugar cane vendors abound, also refreshing in the heat. Tea and coffee are ubiquitous of course. Often, upon entering a house you may be offered green tea-a Chinese-derived habit. In cafes, you can also order black tea with lemon. Most Vietnamese prefer to drink tea, but you can easily find coffee, introduced to Vietnam in the 19th century under the French with Vietnam now being only 2nd to Brazil in coffee bean exports. The most common beans are robusta, grown mainly in the Dak Lak province, while arabica beans are grown in Lam Dong. Filter kits are provided to the caffeine-addicted in cafes. The waiter brings an individual filter cup containing a few teaspoonfuls of coffee grains; this sits over the regular cup and you wait about 10 or 15 minutes for piping-hot water to filter through. A variation of this is the French Press. This method mixes coarsely ground coffee and just off-the-boil water for a few minutes, after which the wire mesh filter is plunged through the brew to trap the grounds at the bottom of the pot. The Vietnamese add butter to their coffee to counter the bitter flavor, and some Hanoi cafes serve yolk-cream coffee-egg yolk mixed with sugar and butter. A large dollop of sweetened condensed milk is an ingredient in addictive caphe suda, or iced coffee.

I have a new friend and it is thee, sweet milk Vietnamese cafe

Tea Master Mr. Hoang Anh Suong is the foremost tea expert in Vietnam and a  journalist with deep experience in Buddhism, Zen & Spirit including two months traveling along with Monk Thich Nhat Hanh throughout the U.S. Meet with Suong in his tea house to enjoy special teas, and to learn more about Vietnamese tea culture, Buddhism and Meditation. Suong is fluent in English.

journalist with deep experience in Buddhism, Zen & Spirit including two months traveling along with Monk Thich Nhat Hanh throughout the U.S. Meet with Suong in his tea house to enjoy special teas, and to learn more about Vietnamese tea culture, Buddhism and Meditation. Suong is fluent in English.

The moonshine of Vietnam (at about a whopping 29% alcohol) is called rượu đe (pronounced "roo day") a distilled liquor made of either glutinous or non-glutinous rice. It's most typical of the Mekong Delta region in the south (its equivalent in northern Vietnam is called rượu quoc lui. Be forewarned, if locals ask you to drink it's often done in shots, in quick order to toasts of mot trăm phan trăm (one hundred percent)!

Imported wine is widely available though expensive in Vietnam (local wines can be a challenge except for the sweet dessert varieties). Dalat mulberry wine looks and tastes like port; Sapa wine tastes like a plum wine. Snake wine (complete with a snake in the bottle), is a souvenir offered at all larger markets. You may find some imported Eastern Bloc bottles of champagne on the dusty shelves of a cafe-good for bathing in, but not much else. Beers are cheap and safe to drink. Brasseries et Glacieres d'Indochine (BGI) is a company that brewed in French colonial times, and is back again, this time with local partner Tien Giang. BGI has breweries in Saigon, Mytho, and Danang. Huda, from Hue, is a joint-venture Danish beer; Vinagen is Canadian; Halida is a joint venture with Carlsberg; Tiger Beer comes from Singapore. Popular local brands include 333 and Saigon Export. On the streets, the locals make their own brew, called bia hoi, literally meaning "fresh beer." It's siphoned from a curbside keg and costs under a dollar.

Notes from Vietnam's Culinary Frontier (Top ten dishes in Vietnam)

Our culinary trips began in the early 1990s, mostly hybrid cycling & culinary tours, equal parts travel by two wheels while exploring farms, villages, small towns and meandering coastal and mountain routes, and eating, eating, eating—anyone who knows a cyclist understands just how much they can eat. Not as popular as today, when most people can name their favorite local pho joint, our travelers were surprised and delighted to discover delicious Vietnamese food and snacks in simple street cafes and even living rooms along our route.

Since then, I've spent time in other great culinary places, including Turkey and Japan, but like Bourdain says "Vietnam will always be my first love." During these trips, one after the other, moving slowly from Hanoi all the way to Saigon, a natural affection grew for specific dishes listed below, that are only made in one place, or are the best in that place, such as banh xeo in Hue. Let me mention the lowly French fry here—no fooling, Vietnam has the best fries you will ever dip into chili sauce. In Vietnam they are fried crispy, almost to a potato-chip texture yet still wet with oil. Nouc mam, the ubiquitous fermented fish sauce is splashed into almost every dish. It's pungent and something I never eat outside of Vietnam, but in the humidity of the country it's delicious and addictive. True to the regional differences described already, there are places where cuisine never changed and others where innovation is the rule, driven mostly by tourism, such as Hoi An where early travelers like myself were bribed by local chefs to share ideas for popular eats, including burgers, ketchup, and guacamole, which quickly appeared after the backpackers started arriving. —Patrick Morris

Phở bò Hà Nội

The pho from Hanoi is in the traditional style, with beef stock simmered for hours, in a smallish bowl with only a few ingredients to adorn the lean beef strips. It's not as abundant, bold, or colorful or perhaps even as tasty as the southern style, but its the style I came to like most—simple, clean, and not overdressed.

Bún bò Huế

This spicy soup originated in its namesake city, Hue, a place overlooked not just for it's cuisine but altogether for most travelers miss the truly special places, people, and delicious cuisine in Hue. The spicy kick of Bún bò Hue is tangible, but not so much you don't enjoy the other complex flavors of this unique beef soup.

Cao lầu

A favorite of many visitors, this unique not-to-miss soup is from Hoi An, where its claimed the only true version can be made from the town's water, though ironically is an almost dry soup. Large noodles with with slow-cooked pork, bean sprouts and herbs, with a dash of a strong broth and topped with delicious deep-fried won ton crackers.

Bánh xèo

A stuffed rice pancake or crepe served hot and crispy, filled with pork or prawns, diced green onion, mung bean, bean sprouts, which is then wrapped in lettuce, and add mint, basil, and fish mint. The crunchy crepe is a delight with nuoc cham, a sweet fish and garlic sauce doused over it right before eating. The tastiest comes from Hue. Delicious vegetarian version as well.

Bún thịt nướng

Admittedly this dish is kind of a cheat, simply combining dishes—but what an incredible one, including fried spring rolls, pork cutlet (or shrimp, 5-spice chicken or beef), and cold noodles. Herbs like basil and mint, fresh salad leaves are added and the sauce is straight up nuoc mam (fish sauce), then topped with peanuts and carrots. Of course, regional varieties abound.

Cà phê sua (đá)

Vietnamese drip coffee is a ritual drink, brought to your table in a thin tin set atop a glass that slowly drips hot water infused from coffee from grounds into sweetened condensed milk already in your cup. The taste is sweetly delicious and the rush of sugar and caffeine are immediate. You may find yourself pausing for a few of these a day. Dá (ice) is served during hot weather.

Bún chả

These pork meatballs are the most delicious you'll ever have, served with fresh lettuce, carrot, bean sprouts, herbs, rice noodles, and of course, nuoc cham for dipping. Remember the photo of Obama in Hanoi at the cafe with Anthony Bourdain? It was a bun cha cafe, two blocks form our office.

Chả giò (Fried Spring rolls)

Vietnamese spring rolls are legendary for any traveler who has been to Vietnam. It's a simple recipe–ground meat, usually pork, wrapped in rice paper and deep-fried—but the result is magnificent. After wrapping with large green leaf lettuce, herbs, and dipped into nuoc cham, its one of those things you can't stop popping in your mouth over and over.

Gà xào sả ớt

A spicy lemongrass chicken dish that can be hard to find, but the strong dose of chilies, lemongrass, and fish sauce stir-fried chicken dish is strong in flavor I crave wherever it's offered. Typically served with a pile of moist plain rice to mix it in.

Vegetarian Spring Rolls

Our travelers are always surprised by the many delicious options for eating meat-free in Vietnam. But this shouldn't be, as Vietnamese dishes typically include very little meat regardless. These fresh and raw spring rolls are salad in a delicate rice paper wrap and dipped in sweet nuoc mam.

Mè Xửng Huế

Another treat from Hue. During our trips through through we stop and buy packages of this congealed rice flour, peanuts and sesame seeds. It's a delightful, bite-size and chewy blend of sugar and nuts which create a unique, tasteful flavor. In Hue you find the freshest, largest, and, ahem, most authentic. It's also the perfect food souvenir which you can pack and savor back home..

Cá Kho Tộ

After marinating in nuoc mam and sugar, a filet of catfish is slowly simmered until sauce caramelizes and is then served in a clay pot with scallions and black pepper. The now juicy fillet, in a sauce thick and rich, is an intense flavor bomb to be cut with white rice.

Bia Hoi

Bia hoi, or happy hour, is a racous street in Hanoi every workday afternoon with curbside tables filled by workers drinking pitchers of local draft beer served with small snack bowls. The people watching and meeting makes this an event not to miss.

Green Papaya Salad

Originally from Laos, and popular in Thailand (som tum) with a uniquely Vietnamese take being typically served with delicious strips of lean beef, rather than shrimp. Also tasty in vegetarian style with cooked tofu.

Che (đá)

Che is an exotic dessert drink, made in various versions that might include tapioca, mung bean, corn, nuts, condensed or coconut milk, jackfruit, lychees, longan, pandan jelly, with ice thrown on top and then mixed in for unique sweet concoction not found outside of Vietnam.Books and Online about Vietnamese Cuisine

The dynamic food scene changes constantly in Vietnam, but browse a few of our restaurant recommendations in Saigon and also restaurants in Hanoi. Much of our traveler's dining or "food adventuring," including kitchen tours, reservations and transport, is planned well before arrival, dependent on preferences and recommendations.

![]() Download an older copy of our Vietnam Dining Guide

Download an older copy of our Vietnam Dining Guide

Luke Nguyen and Vietnam's biggest fan for food and almost everything else, Anthony Bourdain, have many entertaining pieces from travel in Vietnam, focused on cuisine, on YouTube. Bourdain also has a book with sections on Vietnam in his Chef’s Tour. The now rare World Food Vietnam by Richard Sterling (Lonely Planet) is no longer published and if you find a rare copy, it’s a great resource on Vietnam, regardless of cuisine. Below are a few of our favorite Vietnamese cooking books.

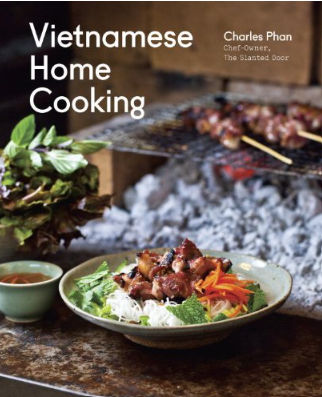

Vietnamese Home Cooking by Charles Phan

Vietnamese Home Cooking by Charles Phan

Disclaimer: We've eaten at the Slanted Door in San Francisco more times than can be counted and know the Phan family personally, but nonetheless Phan is a legend—starting out with a small fringe neighborhood restaurant to be a driving force for popularizing Vietnamese cuisine in America, while building up what would become the most popular restaurant in San Francisco and the top Vietnamese restaurant in the U.S. Phan's book features street-food recipes, which he grew up around. Fresh, simple ingredients, transformed curbside and stalls into delicious dishes sold cheaply for legions of workers who have little time, nor space to cook at home. A good balance with Luke Nguyen's book below, which is more travelogues, Phan's recipe recipes are divided between techniques: Steaming, braising, grilling, and stir-frying, soup and street food. If you've dined at the Slanted Door, Phan also wrote a book on their recipes: The Slanted Door: Modern Vietnamese Food.

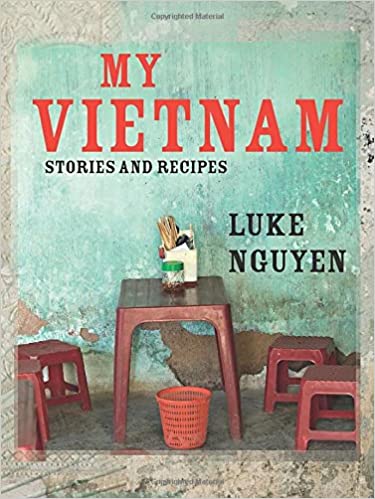

My Vietnam by Luke Nguyen

If you haven't yet, pull up Luke's delightful food adventuring videos on YouTube. Aussie born Luke is proud of his Vietnamese culture, especially the cuisine and has created television shows and now has published this book and others, including Food of Vietnam. This oversize book is part travelogue, which Luke excels in, part autobiography, and part a cookbook of favorite recipes, with vivid photographs of people, places, and food, with a clean layout and pleasant graphics. If you only collect a couple books on Vietnam, this should be one—a perfect souvenir or gift for the coffee table. Luke also categorizes the chapters by cities, which makes the most sense for Vietnam, with marked regional differences of dishes, but he also gives you a sense about what each place is about and his descriptions are colorful and the flow of the book moving from Hanoi to Ho Chi Minh City like a guidebook and the order in which we almost always organize our trips.

If you haven't yet, pull up Luke's delightful food adventuring videos on YouTube. Aussie born Luke is proud of his Vietnamese culture, especially the cuisine and has created television shows and now has published this book and others, including Food of Vietnam. This oversize book is part travelogue, which Luke excels in, part autobiography, and part a cookbook of favorite recipes, with vivid photographs of people, places, and food, with a clean layout and pleasant graphics. If you only collect a couple books on Vietnam, this should be one—a perfect souvenir or gift for the coffee table. Luke also categorizes the chapters by cities, which makes the most sense for Vietnam, with marked regional differences of dishes, but he also gives you a sense about what each place is about and his descriptions are colorful and the flow of the book moving from Hanoi to Ho Chi Minh City like a guidebook and the order in which we almost always organize our trips.

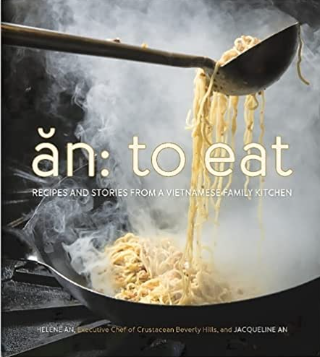

ăn: to eat by Helene and Jacqueline An

Our favorite. A beautiful book on Vietnamese cuisine, with practical sections on kitchen tools, herbs, and techniques. The An sisters, of the California-Vietnamese family that fled Vietnam by boat with nothing, founded a string popular restaurants, including Crustacean in Beverly Hills, have published this book featuring family history, stories, and recipes that include not only versions traditional favorites such as beef pho, but a fusion of French and California cuisine into a modern Vietnamese style. The recipes are the best of Vietnamese cooking, laid out in easy-to-follow-fashion. In our opinion, traditional Vietnamese food is as enjoyable outside of the country, missing the setting (often curbside), the ingredients only found there, and the freshness, so one may as well indulge in innovative variations that expand on the traditional versions. This book is perfect for this and the photography is the best of any of the Vietnamese cookbooks we've read.

Our favorite. A beautiful book on Vietnamese cuisine, with practical sections on kitchen tools, herbs, and techniques. The An sisters, of the California-Vietnamese family that fled Vietnam by boat with nothing, founded a string popular restaurants, including Crustacean in Beverly Hills, have published this book featuring family history, stories, and recipes that include not only versions traditional favorites such as beef pho, but a fusion of French and California cuisine into a modern Vietnamese style. The recipes are the best of Vietnamese cooking, laid out in easy-to-follow-fashion. In our opinion, traditional Vietnamese food is as enjoyable outside of the country, missing the setting (often curbside), the ingredients only found there, and the freshness, so one may as well indulge in innovative variations that expand on the traditional versions. This book is perfect for this and the photography is the best of any of the Vietnamese cookbooks we've read.

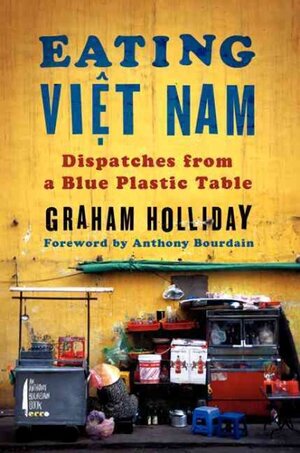

Eating Vietnam by Graham Holliday

For the young and adventurous backpacker in your family. Vietnamese dining can be very fine, savored in elegant French villas on white tablecloths with imported French wines, but is for the most part unpretentious and the best and most delicious dishes savored in atmospheric streets and alleyways, sitting atop kid's chairs over "blue plastic tables" and which is the focus of Graham Holliday's "street food" journeys. Graham lived in Vietnam and his lively (and be forewarned, gritty) stories not only document his street food experiences from Saigon to Hanoi, but his adventures as an ex-pat trying to forage a life as a food blogger frequently infused with his unique experiences and keen observations as a foreigner in the Land of Nine Dragons. Published by Anthony Bourdain and written very much in the style of his food and travel stories.

For the young and adventurous backpacker in your family. Vietnamese dining can be very fine, savored in elegant French villas on white tablecloths with imported French wines, but is for the most part unpretentious and the best and most delicious dishes savored in atmospheric streets and alleyways, sitting atop kid's chairs over "blue plastic tables" and which is the focus of Graham Holliday's "street food" journeys. Graham lived in Vietnam and his lively (and be forewarned, gritty) stories not only document his street food experiences from Saigon to Hanoi, but his adventures as an ex-pat trying to forage a life as a food blogger frequently infused with his unique experiences and keen observations as a foreigner in the Land of Nine Dragons. Published by Anthony Bourdain and written very much in the style of his food and travel stories.

Rogues: Journeyman: Anthony Bourdain by Patrick Radden Keefe

On Bourdain's love of Vietnam and the bun cha meal with President Obama in Hanoi.

"Several years ago, he seriously considered moving there. Bourdain believes that the age of the fifteen-course tasting menu “is over.” He is an evangelist for street food, and Hanoi excels at open air cooking. It can sometimes seem as if half the population were sitting around sidewalk cook fires, hunched over steaming bowls of phở."

For a standout blog, the longtime Hanoi-based Sticky Rice is a deep dive into the city's street eats.

Ready to plan your culinary trip to Vietnam? Click below or call us at (415) 418-6800